This story update is part of the Outside Classics, a series highlighting the best writing we’ve ever published, along with author interviews and other exclusive bonus materials. Get access to all of the Outside Classics when you sign up for Outside+.

In February 2010, a trainer at SeaWorld Orlando named Dawn Brancheau was working with Tilikum, a 22-foot-long, 12,000-pound orca, when the creature took her ponytail in his mouth, dragged her to the bottom of the pool, and shook her like a dog with a toy. By the time rescuers could extract Brancheau, she was dead.

The Killer in the Pool

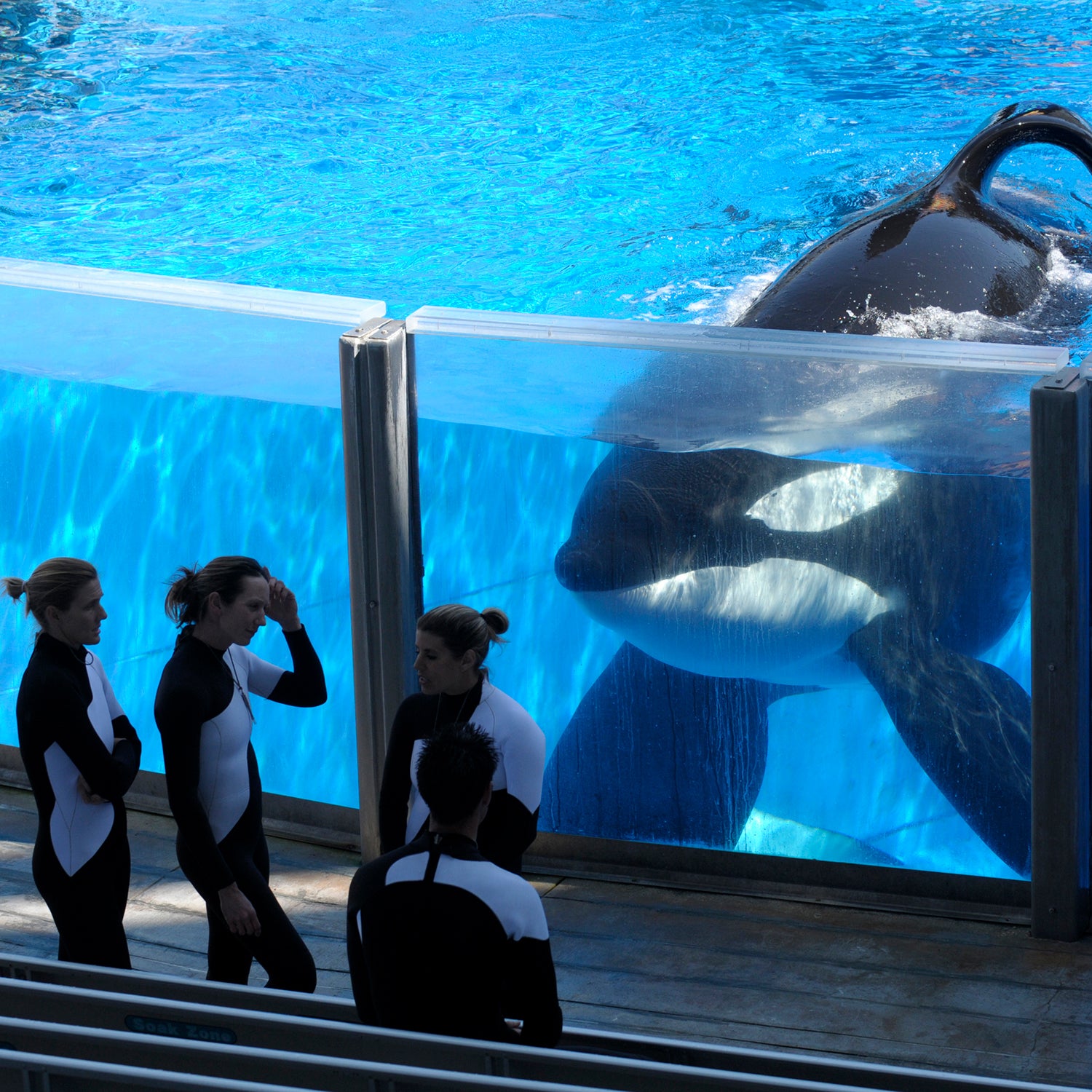

He glanced through the glass and saw Tilikum staring back, with what appeared to be two human feet hanging down his side. There was a nude body draped across Tilikum’s back.Outside correspondent Tim Zimmermann, who was nominated for a National Magazine Award for his 2005 feature “Raising the Dead,” began looking into what happened. What he discovered was shocking. Orcas like Tilikum—many of them captured as calves and separated from family pods that live together for decades—had been taken from the ocean to live in a marine park’s concrete pools, where the tight conditions lead to boredom, agitation, conflict with other killer whales, and frequent infections. When Brancheau died, Tilikum had been in captivity for nearly 27 years. Hers was the third human fatality he’d been involved in.

Zimmermann’s resulting story, “The Killer in the Pool,” had a profound impact on marine parks, the safety of trainers, and the future lives of captive orcas. His passionate reporting on the topic continued with more stories for Outside, including a 2011 feature about trainer Alexis Martínez, who was killed by an orca at a marine park in Spain’s Canary Islands, and a 2014 piece about the efforts to free a wild-caught killer whale named Lolita at Miami’s Seaquarium.

Gabriela Cowperthwaite, director of the 2013 documentary Blackfish, took notice. After reading Zimmermann’s story about Tilikum, she reached out to him to work on the film, which went on to make millions of Americans aware of the conditions of orcas in captivity.

By this point, SeaWorld and other U.S. marine parks had stopped capturing the animals but had continued a breeding program that ensured generations of captive killer whales. Thanks largely to public pressure inspired by Blackfish, SeaWorld announced in 2016 that it would end its orca breeding program altogether. “Tim’s decision to focus on Tilikum’s psychological health was brilliant, and I’m so proud that his exceptional reporting led to positive changes for these intelligent, beautiful creatures,” says Outside deputy editor Mary Turner, who worked with Zimmermann on the piece. “It’s one of the most important stories that we’ve ever published.”

Tilikum died in 2017, succumbing to a bacterial lung infection, one of the conditions that orcas can contract in captivity. As Zimmermann wrote in an obituary about the whale: “He did not choose the world he lived in, but he survived long enough to change it.” Thanks to Tilikum’s story and Zimmermann’s writing, marine theme parks will never be the same.

Zimmermann talked with Outside contributing editor Elizabeth Hightower Allen from his home in Washington, D.C., where he sails and writes about his adventures in his blog Sailing into the Anthropocene.

Outside: What was it about Tilikum and Dawn Brancheau’s death that made you want to tell their story?

Zimmerman: I knew next to nothing about SeaWorld or killer whale captivity. But what caught my attention was that Tilikum had killed two other people previously. I immediately thought, Whoa, there’s some backstory here. I immediately went to the idea that I wanted to tell that killer whale’s life story, to see why it had been responsible for three human deaths. It didn’t take long before I started to realize that there are lots of reasons that a killer whale in captivity might injure somebody.

I was amazed at how hard it seemed to talk to anybody about life for captive killer whales. I thought, I’ll just call up some former trainers at SeaWorld, and they can talk about it. But I immediately hit a wall. That always triggers your instincts as a curious reporter. Once you start pulling on that string, you’re off and running. It turned into a fascinating story about our relationship with marine mammals, how we view them, and what it was like for Tilikum to go from being a young killer whale off the coast of Iceland to living in a variety of marine parks.

The hardest part of the story for me to read was when his early trainers talked about how friendly Tilikum was, how eager he was to learn. Then you think of his life from there. As you worked on the story, did you get sadder and sadder or madder and madder?

I didn’t get sad, and I don’t think I got mad. What I got was really determined to blow this story up. You’re shocked, because the perception around marine parks was that it’s all about family fun. Nothing seems to be wrong. But then when you start to learn how many marine parks operate, how they train killer whales, how the killer whales are from all different sorts of cultures, and how hard it is to maintain stability amid those groups, it’s really eye-opening.

At what point in your reporting did you reach out to SeaWorld, and what was their reaction?

Very early on. Initially SeaWorld was very open to speaking with me. They had enjoyed 40 years of positive publicity. Dawn Brancheau’s death was a terrible tragedy, and it was shocking for SeaWorld. I visited the park and spoke to multiple trainers still working there about official protocols, that it was a terrible accident. It was when we did the fact-checking that SeaWorld’s management realized I was also telling another side of the story.

Can you walk us through how Blackfish arose from your story about Tilikum?

Filmmaker Gabriela Cowperthwaite read “The Killer in the Pool” and thought it would make a great documentary. She called me up out of the blue. Often with Outside stories, people call up and say, “Hey, I want to make a movie about this.” My attitude has always been, “Great. When you raise the money, let’s go.” And they never call back. But Gabriela had the funding. She was very generous about inviting me to participate. I was kind of the road map to the whole thing—I had gone from zero to a hundred in terms of my understanding of SeaWorld and Tilikum’s story. She and her crew were still at zero.

One thing that happened after “The Killer in the Pool” is that all these trainers started to reach out to each other. They organized an annual meeting in Washington’s San Juan Islands, calling it Superpod, the term for a large gathering of orcas. Gabriela and I went and interviewed trainer after trainer. By the end, Gabriela and the team were at a hundred in terms of their knowledge of SeaWorld.

Blackfish went on to have a huge impact, not just on audiences but on SeaWorld itself.

For me it was a big eye-opener about the power of film. I came to the story as a magazine writer. And 90 percent of what’s in Blackfish is in “The Killer in the Pool.” It was a widely read story, but when Blackfish came out, all of a sudden everyone was like, Oh my God, do you know what happened at SeaWorld?

When it first went into theaters, friends would call and say, “I’m watching the documentary,” and I’d ask, “How many people are there?” And they’d say, “About thirty.” But then CNN Films bought the documentary at Sundance. They aired it on a Sunday night, and then, because it’s cable, they aired it over and over and over. That’s when it just exploded into the national consciousness.

Did you hear anything from SeaWorld about the film?

In April 2014, SeaWorld put up a Facebook post, “69 Reasons You Shouldn’t Believe Blackfish,” that linked to a 32-page analysis of the film’s supposed inaccuracies. Gabriela, the Blackfish team, and I immediately did a 69-point rebuttal. It wasn’t a winning battle for them. Celebrities started tweeting. Acts like the Barenaked Ladies and Willie Nelson canceled shows at SeaWorld. That’s when you started to see the stock price drop, and SeaWorld began suffering actual commercial damage. Southwest Airlines ended its collaboration with them, and they weren’t getting as many people through the gates.

It must have been amazing to see that impact. In 2016, SeaWorld announced that it would end its captive-orca breeding program and phase out killer whale performances.

Ending the breeding was huge. By ending it, SeaWorld essentially committed to ending its killer whale program. Of course, it will take decades before every last killer whale dies at SeaWorld. But still, it was a humongous shift—a complete change in their business model. It was the maximum goal of activist campaigns for decades.

The reality is, there’s nothing else they can do with most of those orcas. Most have been in captivity so long, it’s hard to know how they’d do in the wild. There are projects now to build sanctuaries for killer whales and belugas and dolphins, but they are moving slowly, and they didn’t exist at the time.

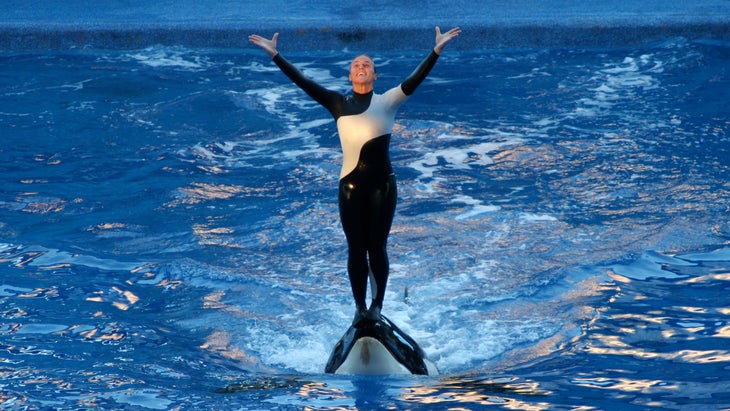

I have to admit that when I visited SeaWorld and saw a show, it was spectacular entertainment. There’s no question about that. After Brancheau died, they tried to make the shows more educational; they were no longer these spectacular circus-style performances, but they still involved killer whales jumping and splashing. The fact that they’re not breeding anymore and their orca group will eventually die off over the decades—that’s a huge deal.

Have the conditions changed for orcas in captivity?

If you’re an orca, your life hasn’t changed much since Blackfish. The reality and the physics of being an orca in a marine park can’t really change. Two of the saddest situations are a lone female called Kiska in Marineland in Ontario, who’s been by herself for years now, and a killer whale called Lolita, who was captured in Puget Sound in 1970 and lives in a tiny little tank all by herself at the Miami Seaquarium.

Lolita’s story is so sad. I read that Washington State’s Lummi tribe and other animal activists have unsuccessfully petitioned to move her to a sea pen, where she could be in acoustic contact with her mother and siblings, who still live in the wild. I thought, I can’t read about this anymore. I just can’t take it.

It’s heartbreaking, but those conditions have been known for years. And nothing has really changed. SeaWorld has recovered, and its stock price is high again. Blackfish didn’t end the industry. It helped focus attention on orca captivity in North America and Europe, but in China, they’re building marine parks one after the other, and until recently Russian fishermen were still capturing wild orcas to sell. The sensibility that Blackfish inspired in the West has not taken hold.

Sadly, even if you could send Lolita back to the Pacific Northwest, there’s a good chance she wouldn’t survive the journey. I don’t know that there is necessarily a happy ending for her. There wasn’t for Tilikum. For him, it was just a matter of time.

What about you? I know the story affected you a great deal.

“The Killer in the Pool” made me hyperaware of a specific animal-welfare issue. I have a very logical brain, so I thought, OK, if I care about killer whales, I’m going to care about farm animals, and I’m not going to eat meat anymore. That was simple enough—I like eggs and cheese, so it’s pretty easy to be a vegetarian in my view. But the more I learned, the more I realized that the whole structure of our relationship with animals is completely flawed.

I went from being an oblivious omnivore to a vegetarian to a vegan. That started with the idea that, if I care about Tilikum, I have to care about how we treat other sentient animals. But as a writer, it’s difficult to get people to step back from their lives and change how they fundamentally impact the world around them. You have to give up the idea of a home run and focus on what you can do and how you live.

Yet you fundamentally impacted the safety of marine-park trainers and the future of a whole massive, beautiful species.

I will always carry that and feel proud of that. I’m also always wishing more happened.

What’s your hope for orcas now?

There’s a really interesting situation off the coast of Spain, where a group of killer whales are ramming and disabling sailboats. All these experts are hypothesizing about why this is happening, why these orcas are predictably and routinely going after boats. Some people are saying, They’re finally fed up with us, but no one really knows. It just makes me happy to know that killer whales are still out there doing their own thing for reasons we simply cannot understand. They are still an alien, intelligent species. No matter what we think we know about the planet and other species, there are still some mysteries left. I have no idea why those orcas are doing what they’re doing. But more power to them.