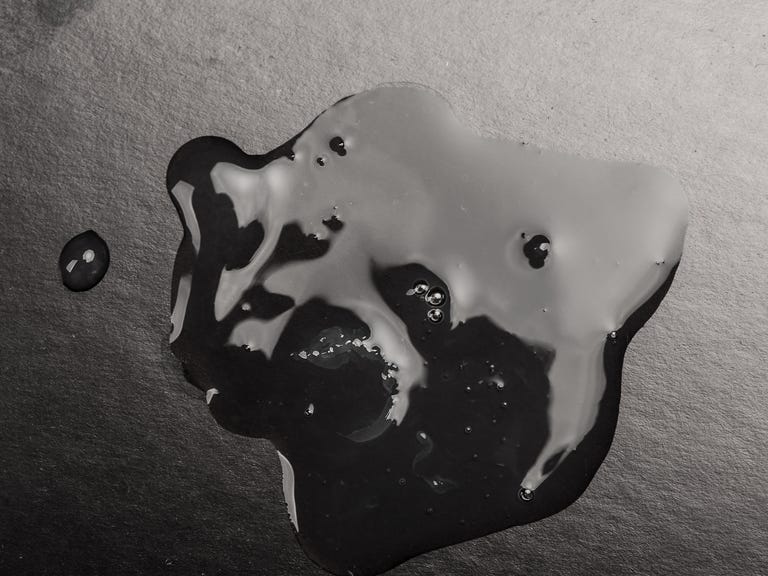

It goes by many names: “La Mancha Negra,” “The Black Spot,” or even just the “Mysterious Black Goo.” No matter what you call it, this mysterious phenomenon has been terrorizing the streets of Caracas, Venezuela since the mid-1980s, causing deadly road accidents.

Or has it?

Searching online for evidence of La Mancha Negra yields surprisingly few results. Although, what it lacks in primary sources, it makes up for in conspiracy theories about what really happened almost 40 years ago, when the sticky, black substance first appeared. Theories ranging all the way from aliens to oil seepage and political sabotage have been proposed, though the truth remains somewhat of a mystery—even to the experts.

“This is a really old story and there are lots of myths and realities about this,” Ramanan Krishnamoorti, Ph.D., a professor of chemical and petroleum engineering at the University of Houston, tells Popular Mechanics. “The size and scope and timing of the ‘oozing’ and then the repetition after five years made for a real mystery.”

Here’s everything you need to know about La Mancha Negra, and why the curious black sci-fi–like substance is so hard for scientists to pin down.

A Brief History of La Mancha Negra

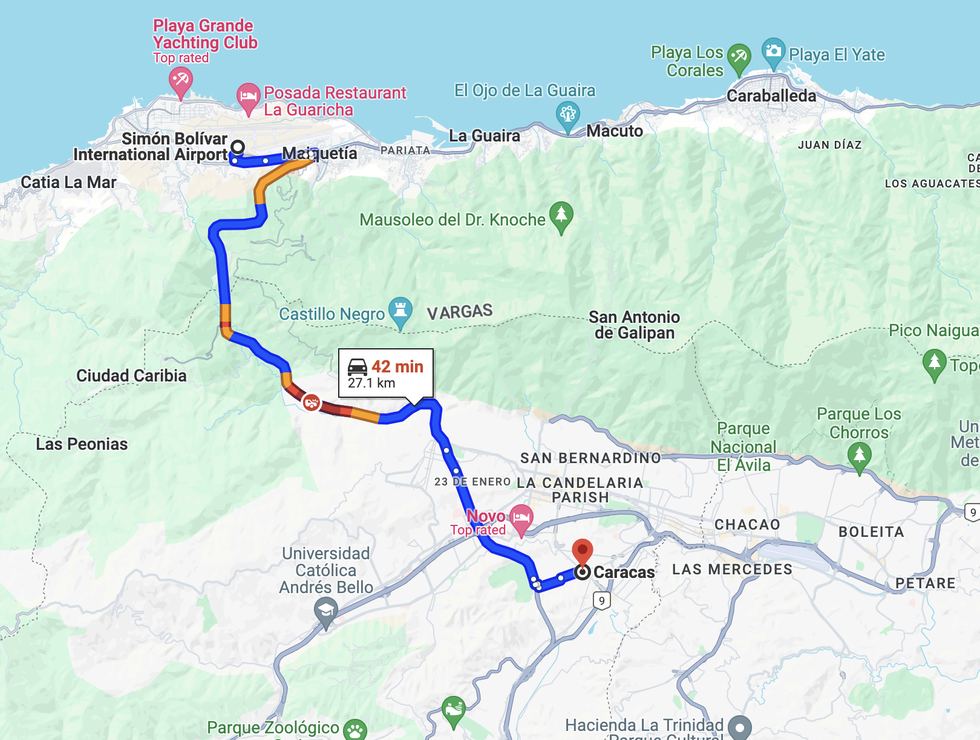

Here’s what we (probably) know about the life and conquests of La Mancha Negra. In 1986, a crew of road workers first noticed black goo on a major highway between the heart of Caracas, Venezuela to the nearest local airport, Simón Bolívar International. Original reporting on the phenomenon from the Chicago Tribune, circa 1992, described the goo as “thick black sludge with the consistency of chewing gum.” Between the spot’s first appearance in the mid-1980s and the Tribune reporting on it in the early 90s, it’s been reported that the spot spread to cover an area of eight miles. It’s also been widely reported that during this period of the spot’s encroachment, it took the lives of 1,800 motorists on the highway, although the Tribune doesn’t attribute this number to a direct source.

A local taxi driver, speaking with the Tribune, described maneuvering on this contradictorily gooey yet slippery substance as being “like driving in a grand prix.”

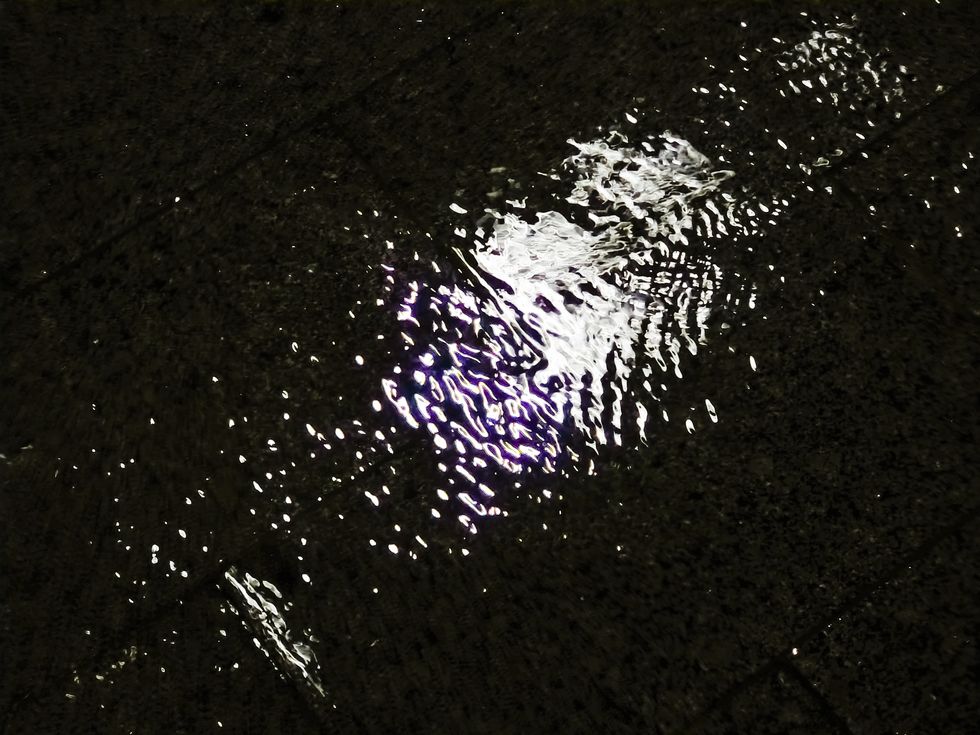

Attempts to remove the goo have employed power washers, scrappers, detergents, and pulverized limestone. And while the spot briefly disappeared later in the 90s, it reappeared again for several years in 2001. During this time, Courrier International, via Venezuela’s El Nacional, wrote that the black goo was measured in some places at almost one inch thick.

But after this Y2K reemergence, the internet trail goes ice cold.

What Do Scientists Think About La Mancha Negra?

After all this time, two theories have floated to the top to describe La Mancha Negra: the effects of subpar asphalt, and the effects of oil seeping up from underground reserves.

Reinaldo Gonzalez, Ph.D., is an adjunct lecturer at the University of Houston in the petroleum engineering department who worked and taught in Caracas during La Mancha Negra’s original appearance. While he admits that his memory of the exact details are hazy, it’s clear, in his opinion, that faulty asphalt was the cause of the messy goo.

“La Mancha Negra appeared on asphalt that was treated with emulsifiers to obtain a product with the same characteristics of regular asphalt used on roads, but [I speculate] with probably reducing costs and allowing other chemical advantages,” Gonzalez tells Popular Mechanics. “The simplest possible explanation that I seem to remember is that the phases of the treated asphalt separated, and one of them ‘emerged’ to the surface, causing a kind of black and slightly greasy stain on the roads.”

Krishnamoorti agrees this theory is more likely than the possibility of oil seeping up from underground reserves.

“Usually such oozing from a reservoir’s subsurface would have to be at a single failure point and not likely to spread over an eight-mile length of the road,” he explains. “Also, typically heavy oils will settle and not try to ooze out onto the surface. Most likely, the bet was on a bad batch of asphalt, [and that] was the consensus.”

But even assuming bad asphalt was the culprit, Krishnamoorti says the situation would still be very odd.

“Degradation of asphalt in the pristine atmosphere is unusual—it is possible that the particular batch had some additional residues or chemicals in the asphalt that allowed it to react and convert based on some atmospheric trigger,” he says. “Typically high temperatures would make the liquid blooming much more easy—remember, even good asphalt can get sticky at high temperatures.”

While Caracas is not as hot as some places around the world, such as India, where melting sidewalks have eaten pedestrians’ shoes, it does maintain an average temperature in the year-round.

Even so, heat alone wouldn’t necessarily be enough to trigger this strange behavior in asphalt, Krishnamoorti says. This may potentially come down to the emulsifiers that Gonzalez recalls. Regardless, Krishnamoorti says cleaning up this asphalt goo would have been difficult, especially considering environmental factors like rain.

“Removing asphalt is tough—it is time consuming, and has to be pretty much dug out—you would completely lose the road, and would have to re-lay it fully,” he says.

Exactly how La Mancha Negra was ultimately defeated is still a mystery, although it may be related to a landslide in the late 90s that necessitated building new roadways in the city.

But at least one thing is certain, according to Gonzalez: “It is not a current problem!”

Sarah is a science and technology journalist based in Boston interested in how innovation and research intersect with our daily lives. She has written for a number of national publications and covers innovation news at Inverse.