Lamna nasus - Cites

Lamna nasus - Cites

Lamna nasus - Cites

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

A. Proposal<br />

Inclusion of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> (Bonnaterre, 1788) in Appendix II in accordance with Article II 2(a) and (b).<br />

Qualifying Criteria (Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP13)) 1<br />

Annex 2a A: It is known, or can be inferred or projected, that the regulation of trade in the species is<br />

necessary to avoid it becoming eligible for inclusion in Appendix I in the near future.<br />

North and Southwest Atlantic and Mediterranean stocks of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> qualify for listing under this<br />

criterion, because their marked decline in population size meets CITES’ guidelines for the application of<br />

decline to commercially exploited aquatic species. The largest global stocks of this low productivity shark<br />

have experienced historical extent of declines to

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

1.3 Family: Lamnidae<br />

1.4 Species: <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> (Bonnaterre, 1788)<br />

1.5 Scientific synonyms:<br />

1.6 Common names:<br />

See Annex 2<br />

English: Porbeagle<br />

Danish: Sildehaj<br />

Swedish: Hábrand; sillhaj<br />

German: Heringshai (market name: Kalbsfisch, See-Stör)<br />

Italian: Talpa (market name: smeriglio)<br />

Spanish: Marrajo sardinero; cailón marrajo, moka, pinocho<br />

French: Requin-taupe commun (market name: veau de mer)<br />

Japanese: Mokazame<br />

2. Overview<br />

2.1 The large warm-blooded porbeagle shark (<strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>) occurs in temperate waters of the North<br />

Atlantic, with smaller stocks in the Southern Oceans. It is highly vulnerable to over-exploitation in<br />

fisheries and very slow to recover from depletion. It is taken in target fisheries and is also an important<br />

retained and utilised component of the bycatch in pelagic longline fisheries. The meat and fins are of high<br />

quality and high value in international trade. Trade records are generally not species-specific;<br />

international trade levels, patterns and trends are largely unknown. DNA tests for parts and derivatives in<br />

trade are available.<br />

2.2 Unsustainable North Atlantic target L. <strong>nasus</strong> fisheries are well documented. These have depleted stocks<br />

severely; landings fell from thousands of tonnes to a few hundred in less than 50 years. Joint assessments<br />

of North and Southwest Atlantic stocks by ICCAT and ICES scientists (2009) have identified marked<br />

historical extents of decline to significantly less than 30% of baseline. Mediterranean CPUE has declined<br />

to less than 5% of baseline. Where data are available for other Southern Hemisphere stocks, which are<br />

also a high value target and bycatch of longline fisheries and are biologically less resilient to fisheries<br />

than North Atlantic stocks, these show a significant recent rate of decline to less than 30% of baseline<br />

(New Zealand) or no trend (Japan southern bluefin area).<br />

2.3 Quota management based on stock assessment and scientific advice has been in place in the Canadian<br />

Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) since 2002 (the stock has now stabilised under a rebuilding plan), and<br />

in the EU since 2008 (with a zero quota since 2010). There has been unrestrictive quota management in<br />

the US since 1999 and in New Zealand since 2004, Argentina requires live bycatch of large sharks to be<br />

released alive. National management measures cannot control high seas catches, where unregulated and<br />

unreported fisheries jeopardize national stock recovery plans. At the time of writing, Regional Fishery<br />

Organisations (RFOs) have not set catch limits for high seas stocks.<br />

2.4 <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> meets the guidelines suggested by FAO for the listing of commercially exploited aquatic<br />

species. It falls into FAO’s lowest productivity category of the most vulnerable species: those with an<br />

intrinsic rate of population increase of 10 years (FAO 2001). Extent and<br />

rate of population declines of the majority of global stocks significantly exceed the qualifying levels for<br />

listing in Appendix II.<br />

2.5 An Appendix II listing is proposed for <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in accordance with Article II.2 (a) and (b) of the<br />

Convention and Res.Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP15). Atlantic stock assessments describe marked historic and<br />

recent declines. Exploitation of smaller stocks in other oceans of the Southern Hemisphere is largely<br />

unmanaged and unlikely to be sustainable.<br />

2.6 An Appendix II listing for <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> will ensure that international trade is supplied by sustainably<br />

managed, accurately recorded fisheries that are not detrimental to the status of the wild populations that<br />

they exploit. This can be achieved if non-detriment findings require that an effective sustainable fisheries<br />

management programme be in place and implemented before export permits are issued, and by using<br />

other CITES measures for the regulation and monitoring of international trade, particularly controls upon<br />

Introductions from the Sea. Trade controls will complement and reinforce traditional fisheries<br />

management measures, thus also contributing to implementation of the UN FAO IPOA–Sharks.<br />

Page 2 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 2<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

3. Species characteristics<br />

3.1 Distribution<br />

In the Southern Hemisphere, in a circumglobal band of ~30–60 o S; in the North Atlantic Ocean and<br />

Mediterranean, between 30–70 o N (Compagno 2001, Figure 2). There are separate stocks in the Northeast and<br />

Northwest Atlantic (these were historically the largest global stocks), likely also in the Mediterranean, and in<br />

the Southeast and Southwest Atlantic. The latter two stocks extend into the Southwest Indian Ocean and<br />

Southeast Pacific, respectively. Other Indo-Pacific stocks have not been identified. Annex 3 lists Range States<br />

and FAO Fisheries Areas (Figure 3).<br />

3.2 Habitat<br />

Epipelagic in boreal and temperate seas of 2–18°C, but preferring 5–10 o C in the Northwest Atlantic (Campana<br />

and Joyce 2004, Svetlov 1978), from the surface to depths of 200m, occasionally to 350–700m. Most<br />

commonly reported on continental shelves and slopes from close inshore (especially in summer), to far<br />

offshore (where they are often associated with submerged banks and reefs). They also occur in the high seas<br />

outside 200 mile EEZs (Campana and Gibson 2008), where they are less abundant. Stocks segregate (at least<br />

in some regions) by age, reproductive stage and sex and undertake seasonal migrations within their stock area.<br />

(Campana et al. 1999, 2001, Campana and Joyce 2004, Compagno 2001, Jensen et al. 2002.) Mature females<br />

tagged off the Canadian coast appear to migrate 2000km south to give birth in deep water in the Sargasso Sea,<br />

Central North Atlantic; pups presumably follow the Gulf Stream to return north (Campana et al. 2010a).<br />

3.3 Biological characteristics<br />

<strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> is active, warm-blooded, relatively slow growing and late maturing, long-lived, and bears only<br />

small numbers of young. It falls into FAO’s lowest productivity category of most vulnerable aquatic species.<br />

Life history characteristics vary between stocks and are summarised in Table 2. Northeast Atlantic sharks are<br />

slightly slower growing than the Northwestern stock. Both northern stocks are much larger, faster growing<br />

and have a shorter life span than the smaller, longer-lived (~65 years old) Southern Oceans porbeagles, which<br />

are therefore of even lower productivity and more vulnerable to overfishing than are North Atlantic stocks.<br />

3.4 Morphological characteristics<br />

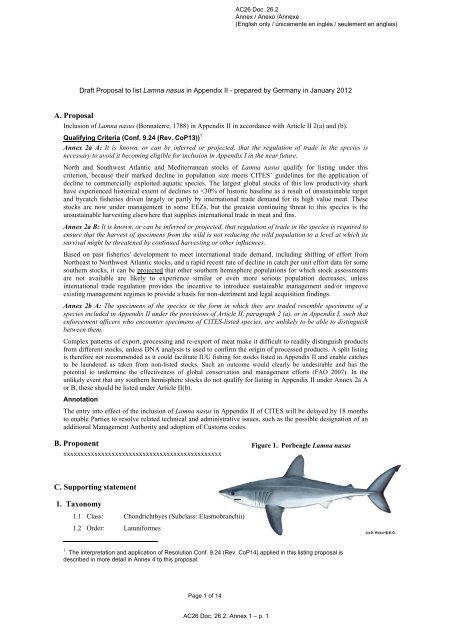

Heavy cylindrical body, conical head and crescent-shaped tail (Figure 1). First dorsal fin has a distinctive<br />

white patch on the lower trailing edge.<br />

3.5 Role of the species in its ecosystem<br />

An apex predator, feeding on fishes, squid and some small sharks, but not on marine mammals (Compagno<br />

2001, Joyce et al. 2002). It has few predators other than humans, but Orcas and White Sharks may take it<br />

(Compagno 2001). DFO Canada (2006) could not demonstrate an ecosystem role at present low levels.<br />

Stevens et al. (2000) warn that the removal of top marine predators may have a disproportionate and counterintuitive<br />

impact on fish population dynamics, including by causing decreases in some prey species.<br />

4. Status and trends<br />

4.1 Habitat trends<br />

Critical habitats and threats to these habitats are largely unknown, although some North Atlantic mating<br />

grounds have been identified. High levels of ecosystem contaminants (PCBs, organo-chlorines and heavy<br />

metals) that bio-accumulate and are bio-magnified at high trophic levels are associated with infertility in<br />

sharks (Stevens et al. 2005), but their impacts on L. <strong>nasus</strong> is unknown. Effects of climatic changes on world<br />

ocean temperatures, pH and related biomass production could potentially impact populations.<br />

4.2 Population size<br />

Effective population size (as defined in Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP14) Annex 5), is best defined by the<br />

number of mature females in the population, particularly in heavily fished stocks dominated by immatures or<br />

males 2 . The only stock for which population size data are available is in the Northwest Atlantic. Recent stock<br />

2<br />

The FAO guidance for evaluating commercially aquatic species for listing in CITES (FAO 2001) stresses the<br />

importance of this consideration.<br />

Page 3 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 3<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

assessments (DFO 2005a, Campana and Gibson 2008, Campana et al. 2010b, ICCAT/ICES 2009, Figure 13)<br />

estimated the total population size for this stock as 188,000–195,000 sharks (22–27% of original numbers<br />

prior to the fishery starting; possibly 800,000 to 900,000 individuals) but only 9,000–13,000 female spawners<br />

(12–16% of their original abundance and 83–103% of abundance in 2001). Stock size elsewhere is unknown.<br />

4.3 Population structure<br />

Genetic studies identified two isolated populations, in the North Atlantic and the Southern oceans (Pade et al.<br />

2006). Tagging studies in the Atlantic support two distinct Northwest and Northeast Atlantic stocks. Long<br />

distance movements occur within each stock, with fish tagged off the UK recaptured off Spain, Denmark and<br />

Norway, travelling up to 2,370km. ADD RESULTS FROM SOSF FUNDED TAGGING WORK IN PREP.<br />

Only one tagged shark crossed the Atlantic (Ireland to eastern Canada, 4,260km) (Campana et al. 1999,<br />

Kohler & Turner 2001, Kohler et al. 2002, Stevens 1976 & 1990). Porbeagles tagged in Canadian waters<br />

move onto the high seas for unknown periods of time (Campana and Gibson 2008), including to pupping<br />

grounds in the Sargasso Sea (Campana et al. 2010a). Stock boundaries in the Southern Hemisphere are<br />

unclear. The Southwest and Southeast Atlantic stocks appear to extend into the adjacent Pacific and Indian<br />

Oceans. The structure of exploited populations is highly unnatural, with very few large mature females<br />

present. This results in an extremely low reproductive capacity in heavily fished, depleted stocks (e.g.<br />

Campana et al. 2001).<br />

4.4 Population trends<br />

Population trends, summarised in Table 3, are presented in the context of Annex 5 of Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP15)<br />

and FAO (2001). The estimated generation time for L. <strong>nasus</strong> is at least 18 years in the North Atlantic, and 26<br />

years in the Southern Oceans (Table 2). The three-generation period against which recent declines should be<br />

assessed is therefore 54 to 78 years, greater than the historic baseline for most stocks. Trends in mature<br />

females (the effective population size 2 ) must be considered where possible. Stock assessments for this species<br />

usually show a correlation between declines in landings, declining catch per unit effort (CPUE), and reduced<br />

biomass because market demand and prices have always been high and there has, until recently, been little or<br />

no restrictive management. Where no stock assessments are available, CPUE, mean size and landings are<br />

therefore used as metrics of population trends.<br />

Figure 2. Available decline trends for porbeagle <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> stocks (from FAO 2010 and other sources<br />

cited in Section 4, Status and Trends)<br />

Stock declines from historic baseline are indicated in black, more recent declines that have occurred during<br />

the past 3 generations (50 years) in grey. A range is indicated where appropriate for some stock assessment<br />

model results. The coloured sections identify decline thresholds to within

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

Table 1. Key to index of percentage decline illustrated in Figure 2.<br />

Index Trend (to % of<br />

baseline<br />

Northeast Atlantic<br />

1 All landings 13%<br />

2 Norwegian landings 1%<br />

3 Danish landings 1%<br />

4 Recent French catch per unit<br />

effort (CPUE)<br />

5 Biomass (surplus production<br />

model)<br />

6 Biomass (age structured<br />

production model)<br />

7 Stock abundance (age<br />

structured production model)<br />

Mediterranean<br />

66%<br />

15-39%<br />

6%<br />

7%<br />

8 All observations 1%<br />

9 Ligurian Sea catches 1%<br />

10 Ionian Sea CPUE 2%<br />

Page 5 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)<br />

Index<br />

Northwest Atlantic<br />

Trend (to % of<br />

baseline<br />

11 All landings 4%<br />

12 Stock biomass (surplus production<br />

model)<br />

32%<br />

13 Stock abundance (age structured<br />

production model)<br />

22-27%<br />

14 Mature female abundance (age<br />

structured production model)<br />

12-16%<br />

Southwest Atlantic<br />

15 Stock biomass (surplus production<br />

model)<br />

18-39%<br />

16 Spawning Stock Biomass (age<br />

structured production model)<br />

18%<br />

Southern Oceans<br />

17 Recent NZ landings 25%<br />

18 Recent NZ longline CPUE 30%<br />

19 Recent Japanese bluefin tuna bycatch<br />

CPUE<br />

no trend<br />

The IUCN Red List status assessment for porbeagle is Vulnerable globally, Critically Endangered in the<br />

Northeast Atlantic and the Mediterranean (past, ongoing and estimated future reductions in population size<br />

exceeding 90%), Endangered in the Northwest Atlantic (estimated reductions exceeding 70% that have now<br />

ceased through management, and Near Threatened in the Southern Ocean (Stevens et al. 2005). Table 1<br />

summarises available information on stock trends from historic baseline and some more recent trend data.<br />

The North Atlantic has historically been the major reported source of world catches, with detailed long-term<br />

fisheries trend data available. Landings here have exhibited marked declining trends over the past 60–70 years<br />

(see below) during a period of rising fishing effort and market demand for this valuable species and improved<br />

fisheries technology. Reported North Atlantic catches (FAO FISHSTAT) during the past decade were less<br />

than 10% of those during the past 50 years (only partly due to the recent introduction of restrictive catch<br />

quotas). Fewer Southern hemisphere data are available (reporting to FAO only commenced in the 1990s), but<br />

some of these also show declining trends. FAO porbeagle catch data (Figure 4) are generally lower than that<br />

from other sources (national landings, ICES data etc.). Under-reporting is widespread, ‘grossly’ so in the<br />

South Atlantic (ICES/ICCAT 2009). Landings from the NAFO Regulatory Area reported to NAFO “seldom<br />

resembled those reported to ICCAT... 2005–2006 catches by countries other than Canada are in doubt and<br />

probably under reported” (Campana and Gibson 2008).<br />

Stock assessments available for the Atlantic (ICCAT/ICES 2009) illustrate the correlation between steep<br />

declines in landings and catch per unit effort (CPUE) and declining biomass. CPUE and landings are therefore<br />

used as indicators of population trends for this valuable commercial species in unmanaged fisheries<br />

elsewhere, while recognizing that other factors may also affect catchability.<br />

4.4.1 North Atlantic and Mediterranean<br />

Most of the fisheries targeting seriously depleted shelf stocks in the Northeast and Northwest Atlantic are now<br />

under stringent management, but not in the Mediterranean. High seas Tuna and Swordfish longline fisheries<br />

also exploit these stocks (as target or retained bycatch) in the NAFO, ICCAT and GFCM regulatory areas,<br />

where porbeagle shark catches remain largely unregulated, except for shark finning bans.<br />

Northeast Atlantic<br />

The Northeast Atlantic age structured production model stock assessment estimated a decline from baseline of<br />

over 90%, to far below the maximum sustainable yield (MSY), at 6% of biomass and 7% of numbers. An<br />

alternative surplus production model estimated that biomass had declined to between 15% and 39% of<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 5

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

baseline. (ICCAT SCRS/ICES 2009; Figures 10 and 11.) During this period, total landings from the Northeast<br />

Atlantic declined to 13% of their 1930s levels.<br />

<strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> has been fished by many European countries, principally Denmark, France, Norway, Faroes and<br />

Spain (Figures 5–9). Norway’s target L. <strong>nasus</strong> longline fishery began in the 1920s and first peaked at 3,884t in<br />

1933. About 6,000t were landed in 1947, when the fishery reopened after the Second World War, followed by<br />

a decline to between 1,200–1,900t from 1953–1960. The collapse of this fishery led to the redirection of<br />

fishing effort by Norwegian, Faroese and Danish longline shark fishing vessels into the Northwest Atlantic<br />

(see below). Norwegian landings from the Northeast Atlantic subsequently decreased to a mean for the past<br />

decade of 20t, 99.99% during a range of time series (135 to 56<br />

years). FAO Fishstat (2009) records very small landings since the 1970s by Malta, in recent years also Spain.<br />

In the North Tyrrhenian and Ligurian Sea, Serena and Vacchi (1997) reported only 15 specimens of L. <strong>nasus</strong><br />

during a few decades of observation. Soldo and Jardas (2002) reported only nine records in the Eastern<br />

Adriatic from the end of 19 th century until 2000. Since then there have been only a few new records (A. Soldo<br />

unpublished data). Newborn and juvenile L. <strong>nasus</strong> have been reported in the Western Ligurian and central<br />

Adriatic Seas (Orsi Relini and Garibaldi 2002, Marconi and De Maddalena 2001). No L. <strong>nasus</strong> were caught<br />

during research into western Mediterranean swordfish longline fishery bycatch (De La Serna et al. 2002).<br />

Only 15 specimens were caught during research conducted in 1998–1999 on bycatch in large pelagic fisheries<br />

(mainly driftnets) in the southern Adriatic and Ionian Sea (Megalofonou et al. 2000).<br />

Northwest Atlantic<br />

Detailed stock assessments and recovery projections are available (DFO 2005; Gibson and Campana 2005;<br />

Campana and Gibson 2008; ICCAT SCRS/ICES 2009; Campana et al. 2010b). Spawning stock biomass<br />

(SSB) is currently estimated to be about 22–27% of its size in 1961. The estimated number of mature females<br />

in 2009 is in the range of 11,000 to 14,000 individuals, or 12% to 16% of its 1961 level and just 6% of the<br />

total population (ICCAT/ICES 2009; Campana et al. 2010b).<br />

Targeted <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> fishing started in 1961, when Norwegian and subsequently Faeroese shark longline<br />

fleets moved from the depleted Northeast Atlantic to the coast of New England and Newfoundland. Catches<br />

increased rapidly from ~1,900t in 1961 to > 9,000t in 1964 (Figure 12). By 1965 many vessels had switched to<br />

other species or fishing grounds because of the population decline (DFO 2001a). The fishery collapsed after six<br />

years, landing less than 1,000t in 1970. It took 25 years for only very limited recovery to take place. Norwegian<br />

and Faroese fleets have been excluded from Canadian waters since 1993. Canadian and US authorities<br />

reported all landings after 1995.<br />

Three offshore and several inshore Canadian vessels entered the targeted Northwest Atlantic fishery in the<br />

1990s. Catches of 1,000–2,000 t/year reduced population levels to a new low in under ten years: the average<br />

size of sharks and catch rates were the smallest on record in 1999 and 2000, catch rates of mature sharks in<br />

2000 were 10% of those in 1992, and biomass estimated as 11–17% of virgin biomass and fully recruited F as<br />

0.26 (DFO 2001a). The annual catch quota was reduced for 2002–2007 to allow population growth (DFO<br />

Page 6 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 6<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

2001a, 2001b) and reduced again in 2006. Landings have since ranged from 139t to 229t. Total population<br />

numbers have remained relatively stable since 2002, although female spawners may have continued to decline<br />

slightly. ICCAT SCRS/ICES (2009) estimated that spawning stock biomass (SSB) is now about 95–103% of<br />

its size in 2001 and the number of mature females 83% to 103% of the 2001 value (Figure 13), or 12–16% of<br />

baseline.<br />

Stock assessments have determined that recovery is possible, but Campana et al. (2010b) warn that the<br />

trajectory is extremely low and sensitive to human-induced mortality. Human-induced mortality of ~2 to 4%<br />

of the vulnerable biomass of 4,500t to 4,800t (equivalent to catching 185–192t in 2005) should allow recovery<br />

to 20% of virgin biomass (SSN20%) in 10–30 years. Recovery to maximum sustainable yield (SSNmsy) will take<br />

much longer: between 2030 and 2060 with no human-induced mortality, or into the 22nd century (or later)<br />

with an incidental harm rate of 4%. At an incidental harm rate of 7% of the vulnerable biomass, corresponding<br />

to a catch of 315t, the population will not recover to SSNmsy (Figures 14 and 15). Campana and Gibson (2008)<br />

also warned that a high seas fishery exploiting this stock jeopardizes Canada’s fisheries management and<br />

recovery plan – the population would crash at these exploitation rates.<br />

In addition to the Canadian quota of 185t, in 1999 a quota of 92t was set in the US EEZ, which is presumed to<br />

share the same stock. The TAC for all US fisheries was reduced to 11t, including a commercial quota of 1.7t,<br />

in 2008. Taiwanese, Korean and Japanese tuna longliners take a largely unknown bycatch of L. <strong>nasus</strong> on the<br />

high seas in the North Atlantic (ICES 2005). Most of the catch is reportedly discarded or landed at ports near<br />

the fishing grounds. Stocks and catches are “under investigation” (Fishery Agency of Japan 2004). Campana<br />

and Gibson (2008) note that the unreported porbeagle bycatch observed on Japanese vessels could have<br />

amounted to ~200t in 2000 and 2001. These levels of combined Northwest Atlantic landings may prevent<br />

stock recovery.<br />

4.4.2 Southern Hemisphere<br />

Observer data from the Uruguayan tuna and swordfish fleet were used to assess the status of the Southwest<br />

Atlantic stock. The assessment identified an 82% decline in biomass (SSB) since 1961, and 60% since 1982,<br />

to well below maximum sustainable level (BMSY) (Figure 19, ICCAT SCRS/ICES 2009), mirroring the decline<br />

in CPUE (Figure 18). This stock probably extends into the Southeast Pacific. Data were not available to<br />

support an assessment of the Southeast Atlantic/Southwest Indian Ocean stock.<br />

FAO FISHSTAT data have been greatly improved in recent years; southern hemisphere catch data are now<br />

available for several countries since the mid 1990s (Figure 20); these show a declining trend, with New<br />

Zealand catches dominating, followed by Spain (which now has a zero quota for porbeagle in EU and<br />

international waters) and Uruguay (FAO FISHSTAT). New Zealand commercial catch, discard and<br />

processing records are illustrated in Figure 16. Volumes processed are sometimes higher than reported<br />

catches. Estimates of tuna longline bycatch are not available for all years and are imprecise because of low<br />

observer coverage. Approximately 60% of longline bycatch is alive when retrieved. Survival of unprocessed<br />

discarded sharks is unknown. About 80% of the bycatch is processed, 80% of this is finned, 20% processed<br />

for the meat and fins (MFSC 2008). There has been a 75% decline in the total weight of L. <strong>nasus</strong> reported<br />

since 1998–99, to a low of 55 t in 2005-06. This decline began during a period of rapidly increasing domestic<br />

fishing effort in the tuna longline fishery, and has accelerated since tuna longline effort dropped during the<br />

last two years. Unstandardised catch per unit effort recorded by observers from 1992–93 to 2004–05 varies<br />

considerably, but has been extremely low in recent years (Figure 17). This may not reflect stock abundance<br />

because of low observer coverage and other potential sources of variation (e.g., vessel, gear, location and<br />

season). [An updated assessment is in preparation and will be incorporated later when available. ]<br />

Japanese tuna longline vessels take an unknown quantity of bycatch of L. <strong>nasus</strong> in the Southern Bluefin Tuna<br />

fishing grounds. Standardised CPUE has varied from 1992 to 2002 but recent stock trends were deemed to be<br />

stable. Current stock levels are under investigation. Most of the catch is reportedly discarded or landed at<br />

ports near the fishing grounds (Fishery Agency of Japan 2004), but do not appear in the FAO FISHSTAT<br />

database. Matsumoto (2005, cited in FAO 2007) reports an increase from very low levels during 1989–1995<br />

followed by a decline in annual landings to around 40% of original levels between 1997 and 2003. Matsunaga<br />

(2009) reported no porbeagle bycatch trend in the same fishery from 1992 to 2007.<br />

4.5 Geographic trends<br />

This species now appears to be scarce, if not absent, in areas of the Mediterranean where it was formerly<br />

commonly reported (Ferretti et al. 2008, Stevens et al. 2006).<br />

Page 7 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 7<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

5. Threats<br />

The principal threat to L. <strong>nasus</strong> worldwide is over-exploitation, in target and bycatch fisheries, which depleted<br />

the world’s largest North Atlantic stocks over 50 years ago (Figure 5). More recently, global reported<br />

porbeagle landings from bycatch and directed fisheries have decreased from 1 719t in 1999 to 722t in 2009,<br />

with the highest catches in 2009 from France (281t), Spain (239t), Canada (63t) and New Zealand (63t) (FAO<br />

FishStat 2011), although ICCAT/ICES (2009) notes that reported landings “grossly underestimate actual<br />

landings”. Canadian catch data indicates that porbeagle landings have progressively decreased, from a peak of<br />

1400 t in 1995, corresponding with decreasing TAC levels (Campana and Gibson 2008, Figure 20), and an EU<br />

zero quota was adopted in 2010. However, other fisheries are also declining, even in the absence of restrictive<br />

management (for example, in the southern hemisphere (Figure 20). This species is particularly vulnerable to<br />

fisheries because, in the absence of management, these target adults and juveniles of all age classes (Ministry<br />

of Fisheries 2006, Francis et al. 2007). Furthermore, the life history characteristics of Southern Ocean<br />

porbeagles make this population significantly more vulnerable to overfishing than the depleted North Atlantic<br />

populations.<br />

5.1 Directed fisheries<br />

Intensive directed fishing for the valuable meat of L. <strong>nasus</strong> was the major cause of 20 th Century population<br />

declines. ICES (2005) noted: “The directed fishery for porbeagle [in the Northeast Atlantic] stopped in the<br />

late 1970s due to very low catch rates. Sporadic small fisheries have occurred since that time. The high market<br />

value of this species means that a directed fishery would develop again if abundance increased.” A target<br />

fishery for the meat of L. <strong>nasus</strong> still operates in Canada, and short term opportunistic target fisheries occur in<br />

other States, in the absence of management, as and when aggregations are located. There are no high seas<br />

catch quotas for porbeagles although the 2009 ICCAT SCRS/ICES stock assessment meeting recommended<br />

that high seas fisheries should not target porbeagle. L. <strong>nasus</strong> used to be an important target game fish species<br />

for recreational fishing in Ireland and UK. The recreational fisheries in Canada, the US and New Zealand are<br />

very small.<br />

5.2 Incidental fisheries<br />

<strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> is a valuable utilised ‘bycatch’ or secondary target of many fisheries, particularly longline<br />

pelagic fisheries for tuna and swordfish (Buencuerpo et al. 1998), but also gill nets, driftnets, trawls and<br />

handlines. Bycatch is often inadequately recorded in comparison with captures in target fisheries. The high<br />

value of porbeagle meat means that the whole carcass is usually retained and utilised, unless the hold space of<br />

vessels targeting high seas tuna and billfish is limited, when the fins alone may be retained (e.g. New Zealand<br />

and far seas longline fisheries for Southern Bluefin Tuna, and other pelagic fishing fleets operating in the<br />

Southern Hemisphere, see Compagno 2001). ICES (2005) noted: “effort has increased in recent years in<br />

pelagic longline fisheries for Bluefin Tuna (Japan, Republic of Korea and Taiwan Province of China) in the<br />

North East Atlantic. These fisheries may take porbeagle as a bycatch. This fishery is likely to be efficient at<br />

catching considerable quantities of this species.” This was confirmed by Campana and Gibson (2008).<br />

ICCAT/ICES (2009) warned that increased effort on the high seas could compromise stock recovery efforts.<br />

Despite the large amount of oceanic fishing activity that must take a bycatch of L. <strong>nasus</strong> in the Southern<br />

Hemisphere, landings reported to FAO only commenced in 1994 and are relatively low, with the exception of<br />

New Zealand, Spain and Uruguay. Japan’s porbeagle bycatch in southern ocean fisheries is not reported to<br />

FAO, but must be significant: porbeagle was the second most abundant species after blue shark and comprised<br />

5.5% of shark catches in the Japanese tuna fishery in Australian waters (Stevens and Wayte 2008)<br />

Spanish vessels used to take a bycatch in their longline swordfish fisheries, and Uruguay and other countries<br />

(some of which do not report to FAO) have a significant bycatch in longline swordfish and tuna fisheries in<br />

international waters off the Atlantic coast of South America (Domingo 2000, Domingo et al. 2001, Hazin et<br />

al. 2008).<br />

Important but largely unreported bycatch fisheries include demersal longlining and trawling for Patagonian<br />

Toothfish and Mackerel Icefish around Heard and Macdonald Islands and in the southern Indian Ocean (van<br />

Wijk and Williams 2003, Compagno 2001), and the artisanal and industrial longline swordfish fishery within<br />

and outside the Chilean EEZ, between 26–36ºS (E. Acuña unpublished data; Acuña et al. 2002), which<br />

records porbeagle. Hernandez et al. (2008) found that <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> made up 1.7% of all fins tested in the<br />

north-central Chilean shark fin trade. Overall catches of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> by Argentina were 30,1 - 17,7 - 19,8 -<br />

69,7 t between 2003 and 2006 (source: INIDEP 2009) (these data do not appear in FISHSTAT), but porbeagle<br />

captures by the Argentinean fleet are probably now limited to incidental captures by three Patagonian<br />

Page 8 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 8<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

Toothfish fishing vessels, and with strict measures in force to protect sharks in Argentinian waters (live sharks<br />

greater than 1.5 m must be released if caught), catches are likely to be minimal. There are observers on all<br />

Argentinean fleets, and an observer report for sharks (including <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>) will be released later in 2012<br />

(Ramiro Sanchez, pers. comm.).<br />

6. Utilisation and trade<br />

Until recently, a lack of species-specific landings and trade data made it impossible to assess the proportions<br />

of global catches that supply national demand and enter international trade, although the high commercial<br />

value of the species has been documented through market surveys (Fleming and Papageorgiou 1997, Rose<br />

1996, unpublished TRAFFIC Europe 2003 market surveys). Survey findings indicated that the demand for<br />

fresh, frozen or processed L. <strong>nasus</strong> meat and fins is sufficiently high to justify the existence of an international<br />

market, while other products include dried-salted meat for human consumption, oil, and fishmeal for fertilizer<br />

(Compagno 2001). The extent of national consumption versus export by range States can vary considerably,<br />

depending upon local demand. For example, high levels of seafood consumption in Brazil, including by some<br />

Asian communities, makes it likely that porbeagle meat is consumed by domestic markets although fins may<br />

be exported. Other States with lower domestic seafood consumption, such as Uruguay, are likely to export its<br />

landings of porbeagle, mixed with mako, another high value shark meat (Andres Domingo pers. comm.).<br />

Following the introduction by the EU of new species-specific codes in 2010, some international trade data for<br />

this species is now becoming available (albeit only for trade involving the EU).<br />

6.1 National utilisation<br />

L. <strong>nasus</strong> has long been one of the most valuable (by weight) of marine fish species landed in Europe, similar<br />

in value to swordfish meat and sometimes marketed as such (Gauld 1989; Vas and Thorpe 1998; TRAFFIC<br />

Europe market surveys; Vannucinni 1999). Porbeagle may also be utilised nationally in some range States for<br />

liver oil, cartilage and skin (Vannuccini 1999). Low-value parts of the carcass may be processed into<br />

fishmeal. There is limited utilisation of jaws and teeth as marine curios. No significant national use of L.<br />

<strong>nasus</strong> parts and derivatives has been reported, partly perhaps because records at species level are not readily<br />

available, and partly because quantities landed are now so small, particularly in comparison with other shark<br />

species.<br />

The species is utilised for sports fishing in the USA and some EU Member States. Catches are either retained<br />

for meat and/or trophies, or tagged and released. Low levels of L. <strong>nasus</strong> are taken by game fishers off New<br />

Zealand South Island, but estimates of the recreational harvest is unavailable and probably negligible since L.<br />

<strong>nasus</strong> usually occur over the outer continental shelf or beyond (MFSC 2008).<br />

6.2 Legal trade<br />

All international trade in <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> products is unregulated and legal. Prior to 2010, all global trade in<br />

porbeagle <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> products was reported under general Customs commodity codes for shark species and<br />

could not be identified. In 2010, the EU introduced new species-specific Customs codes for fresh and frozen<br />

<strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> (porbeagle) products (excluding shark fins) and amended previous codes covering most shark<br />

species to now exclude this species. Table 4 shows the old and new relevant Customs codes for porbeagle.<br />

There is a considerable market for porbeagle products within the European Union (EU), with EU Member<br />

States having taken 60–75% of FAO’s global records of porbeagle catch in 2006 and 2007 (prior to<br />

establishment of a TAC, which was reduced to zero for EU waters and EU fleets in 2010). EU market demand<br />

must now be met by imports. EU imports and exports of this species in 2010 and 2011, reported in<br />

EUROSTAT, are summarized in Tables 5 and 6 (these do not include internal EU trade). Other<br />

countries/territories do not have species-specific codes in place for trade in this species, and continue to report<br />

its trade under general shark commodity codes, preventing analysis.<br />

The following porbeagle range States were the principal suppliers of fresh and frozen porbeagle meat to the<br />

EU (excluding other EU countries) in 2010 and 2011 (EU importer shown in brackets): South Africa (Italy),<br />

Japan (Spain), Morocco (Spain), Norway (Germany and Denmark) and the Faroe Islands (Denmark). A total<br />

of 45,000kg of porbeagle meat, worth EUR 118,294, was imported during this two year period.<br />

South Africa does not have any directed fisheries for porbeagle, although one or two sharks per trip are<br />

apparently caught in the South African pelagic long-line fishery. Therefore, the high quantities imported from<br />

South Africa into the EU are likely to be derived from foreign flagged vessels fishing outside South Africa’s<br />

EEZ and discharging in South African ports. These may include by-catch of Japanese vessels targeting<br />

southern bluefin tuna or catches of Korean, Taiwanese or other vessels targeting tuna and tuna-like species<br />

Page 9 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 9<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

(Source TRAFFIC East and Southern Africa, 2011). None of these fishing entities report porbeagle catches to<br />

FAO.<br />

Two non-range States (and previously unknown players in the market for this species) also reported exports to<br />

the EU: Senegal and Suriname. However, determining the origin of the meat in trade is fraught with<br />

difficulties (as noted above for South Africa), due to countries fishing in international waters and the<br />

inconsistencies in reporting between different countries (flag State versus port State exports, exports reported<br />

after landing or only after processing etc.).<br />

Average prices of imports ranged from only 1.26 EUR/kg for meat imported from Japan to 3.64 EUR/kg for<br />

meat imported from the Faroe Islands. This is significantly lower than prices reported in earlier years for<br />

porbeagle landed into European ports.<br />

Earlier studies had reported that Canada exports L. <strong>nasus</strong> meat to the US and the EU, Japan exports to the EU,<br />

and EU Member States export L. <strong>nasus</strong> to the US, where it is mainly consumed in restaurants (Vannuccini<br />

1999, S. Campana in litt. to IUCN Shark Specialist Group 2006). L. <strong>nasus</strong> is also imported by Japan (Sonu<br />

1998). The new EU trade data confirm exports from Japan to the EU. In Australia, data on exports of L. <strong>nasus</strong><br />

to the US are grouped with Mako Sharks (Ian Cresswell, CITES Management Authority of Australia, in litt. to<br />

BMU, February 2004). Until targeted Customs control and monitoring systems or compulsory reporting<br />

mechanisms to FAO are established, data on non-European international trade in L. <strong>nasus</strong> products will not be<br />

available.<br />

The EU also reported significant exports of porbeagle, particularly in 2010 (68,200kg). These may have been<br />

exports of catches landed and frozen in 2009, before the zero quota, or re-exports. Morocco was by far the<br />

largest destination of porbeagle exported from the EU in 2010, followed by Afghanistan in 2011. However,<br />

the price of porbeagle exported to Morocco was very low (average 0.69 EUR/kg) compared to 17.81 EUR/kg<br />

for porbeagle exported to China and 3-4 EUR/kg for porbeagle exported to Ceuta (Spanish territory in North<br />

Africa), Andorra, Afghanistan and Switzerland. All exports from the EU were from Spain, except those to<br />

Switzerland which came from Denmark. There were no records of the EU importing porbeagle from Canada,<br />

or of the EU exporting (or re-exporting) to the US, as reported in earlier studies.<br />

EUROSTAT also records intra-EU trade – dispatches (equivalent to exports within the EU) and arrivals<br />

(equivalent to imports). However, due to movement of commodities between EU Member States, the<br />

likelihood of double-counting is high. Also there are often considerable discrepancies between quantities<br />

reported as “arrivals” and “dispatches” within the EU (for example if one Member State only reports value,<br />

and the other just weight). Total amounts of specific commodities in trade are therefore difficult to estimate,<br />

however intra-EU trade data can provide an indication of the most important Member States involved in the<br />

trade. In 2010 and 2011 Italy (72%) and Spain (21%) were the principal destinations for trade of porbeagle<br />

commodities (fresh and frozen) within the EU, and Portugal (45%) and Spain (39%) were the principal<br />

suppliers of products traded within the EU. <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> (Vitello di Mare) was on sale in Venice Fish market,<br />

Italy, in November 2010 for 12.80 EUR/kg (pers. comm. Mats Forslund, WWF-SE).<br />

The US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) holds only 20 records of US trade in <strong>Lamna</strong> species between 1998<br />

and 2010 (seven of these being specifically of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>). Trade involved 13 live specimens for zoos, three<br />

bodies for museums and ~20,000 units of jewellery, teeth, bone or skins (source: TRAFFIC North America).<br />

6.3 Parts and derivatives in trade<br />

Meat: This can be a very high value product, one of the most palatable and valuable of shark species, and is<br />

traded in fresh and frozen form (see sections 6.1 and 6.2).<br />

Fins: Porbeagle appears in the list of preferred species for fins in Indonesia (along with Guitarfish, Tiger,<br />

Mako, Sawfish, Sandbar, Bull, Hammerhead, Blacktip, Thresher and Blue Shark, see Vannuccini 1999), but<br />

was reported to be relatively low value by McCoy and Ishihara (1999, quoting Fong and Anderson 1998). The<br />

large size of L. <strong>nasus</strong> fins nonetheless means that these are a relatively high value product. They have been<br />

identified in the fin trade in Hong Kong and are one of six species (including Makos, Blue, Dusky and Silky<br />

Sharks) frequently used in the global fin market (Shivji et al. 2002). The raw fins are also readily recognised<br />

to species level by fin traders in Chile (Hernandez et al. 2008). New Zealand has established conversion<br />

factors for L. <strong>nasus</strong> for wet fin (45) and dried fin (108) (equivalent to a weight ratio of 2.2% and 0.9%<br />

respectively) in order to monitor quota and establish the size of former catches by scaling up reported landings<br />

(Ministry of Fisheries, 2005). The wet fin weight ratio from the Canadian fishery is 1.8–2.8% (S. Campana<br />

pers. comm., DFO).<br />

Page 10 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 10<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

Others: Porbeagle hides can be processed into leather, and liver oil extracted (Vannuccini 1999, Fischer et al.<br />

1987), but trade records are not kept. Cartilage is probably also processed and traded. Other shark parts are<br />

used in the production of fishmeal, which is probably not a significant product from L. <strong>nasus</strong> fisheries because<br />

of the high value of the species’ meat (Vannuccini 1999).<br />

6.4 Illegal trade<br />

Although no legislation has been adopted by range States or trading nations to regulate national or<br />

international trade in <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>, the increased application of strict quota management (including the EU<br />

zero quota) increases the risk of illegal trade transactions and shipments taking place, particularly in the<br />

absence of trade monitoring and regulation at species level.<br />

6.5 Actual or potential trade impacts<br />

The unsustainable L. <strong>nasus</strong> fisheries described above have been driven by the high value of the meat in<br />

national and international markets. Trade has therefore been the driving force behind the depletion of<br />

populations in the North Atlantic and, with the closure of the major northern fisheries, now threatens Southern<br />

Hemisphere populations. Southern populations are of particular concern because they are intrinsically even<br />

more vulnerable to over-exploitation in fisheries than are the depleted northern stocks.<br />

7. Legal instruments<br />

7.1 National<br />

It has been forbidden to catch and land porbeagle in Sweden since 2004.<br />

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) designated L. <strong>nasus</strong> as<br />

Endangered in 2004 (COSEWIC 2004). The Federal Government of Canada declined to list the species under<br />

Schedule 1 of Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA) because recovery measures were already being<br />

implemented.<br />

7.2 International<br />

‘Family Isurida’ (now Lamnidae, including L. <strong>nasus</strong>) is listed in Annex 1 (Highly Migratory Species) of the<br />

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The UN Agreement on Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly<br />

Migratory Fish Stocks, in force since 2001, establishes rules and conservation measures for high seas fisheries<br />

resources. It directs States to pursue co-operation in relation to listed species through appropriate sub-regional<br />

fisheries management organisations or arrangements, but there has not yet been any progress with<br />

implementation of oceanic shark fisheries management.<br />

<strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> is listed in Annex III, ‘Species whose exploitation is regulated’ of the Barcelona Convention<br />

Protocol concerning specially protected areas and biological diversity in the Mediterranean. This population<br />

was also added in 1997 to Appendix III of the Bern Convention (the Convention on the Conservation of<br />

European Wildlife and Natural Habitats) as a species whose exploitation must be regulated in order to keep its<br />

population out of danger. No management action has yet followed these listings.<br />

L. <strong>nasus</strong> is included in Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS). CMS<br />

is currently developing an instrument for the conservation of migratory sharks, which may in due course<br />

stimulate conservation actions for the species.<br />

L. <strong>nasus</strong> is included in the OSPAR Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-east<br />

Atlantic list of Threatened and/or Declining Species and Habitats. This list, developed under Annex V on the<br />

Protection and Conservation of the Ecosystems and Biological Diversity of the OSPAR Maritime Area,<br />

identifies species and habitats in need of protection or conservation. Proposals for actions, measures and<br />

monitoring that should be undertaken for this species will be considered in late 2009.<br />

8. Species management<br />

8.1 Management measures<br />

The International Plan of Action (IPOA) for the Conservation and Management of Sharks urges all States with<br />

shark fisheries to implement conservation and management plans, but is voluntary. Of the top 20 shark fishing<br />

entities, which account for nearly 80% of the world’s shark catch, only 13 are known to have a National Shark<br />

Plan (Lack and Sant 2011), although FAO (2010) reported that 65% of Members that responded to a survey<br />

Page 11 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 11<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

on the implementation of the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries had Shark Plans in place and 11<br />

RFBs reported that they were assisting in the implementation of the IPOA-Sharks. Porbeagle range and/or<br />

fishing States with Shark Plans include Argentina, Australia, Canada, the EU, Japan, New Zealand, Spain,<br />

Taiwan, Uruguay and USA.<br />

Many RFMOs have adopted shark finning bans. Some RFOs have recently adopted shark resolutions to<br />

support improved recording or management of pelagic sharks taken as bycatch in the fisheries they manage,<br />

but no science-based catch limits. ICCAT has required Parties since 2007 to reduce the mortality of porbeagle<br />

sharks in directed Atlantic fisheries where a peer-reviewed stock assessment is not available. In 2008 the<br />

NAFO Scientific Council was warned that overfishing in the high seas NAFO Regulatory Area was<br />

undermining Canada’s management for porbeagles and would lead to population crash (Campana and Gibson<br />

2008), but Parties decided that shark management was ICCAT’s remit. Although a stock assessment has been<br />

available since 2009, neither ICCAT nor NAFO have adopted proposals to introduce catch limits or prohibit<br />

the retention of porbeagles caught on the high seas. At the time of writing, ICCAT’s Ecological Risk<br />

Assessment for pelagic sharks is in preparation for discussion at an ICCAT meeting on 11-15 th June 2012 in<br />

Portugal. The management of southern porbeagle stocks will require close coordination between RFMOs for<br />

the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean waters and CCAMLR.<br />

In the Northeast Atlantic, the conservation and management of sharks in EU waters falls under the European<br />

Common Fishery Policy (CFP), which manages fish stocks through a system of Total Allowable Catch (TAC<br />

or annual catch quotas) and reduction of fishing capacity. EC Regulation 40/2008 established a TAC for<br />

porbeagle taken in EC and international waters of I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XII and XIV of 581 t<br />

(CEC, 2008). The initial restrictive quota was reduced by 25% in 2009 and a maximum landing size (210 cm<br />

fork length) introduced to protect large females (CEC 2009). In 2010, EC Regulation 23/2010 prohibited<br />

fishing for porbeagle in EU waters and, for EU vessels, to fish for, to retain on board, to tranship and to land<br />

porbeagle in international waters. EC Regulation 1185/2003 prohibits the removal of shark fins and<br />

subsequent discarding of the body. This regulation is binding on EC vessels in all waters and non-EC vessels<br />

in Community waters.<br />

The European Community Action Plan for the Conservation and Management of Sharks (CPOA,<br />

EU COM(2009) 40 final), presented by the European Commission in 2009, sets out to rebuild depleted shark<br />

stocks fished by the Community fleet within and outside Community Waters, including through the<br />

establishment of catch limits for shark stocks in conformity with advice provided by ICES and relevant<br />

RFMOs, release of live unwanted bycatch, increased selectivity of fishing gear, establishment of bycatch<br />

reduction programmes for Critically Endangered and Endangered shark species, and international cooperation<br />

in CMS and CITES with a view to controlling shark fishing and trading. The CPOA’s Shark Assessment<br />

Report pays particular attention to <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>. These measures will be implemented at Community and<br />

Member State level and the Community will seek their endorsement by all relevant RFMOs.<br />

In 2007 Norway adopted ICES advice and banned all direct fisheries for porbeagle. From 2007–2011<br />

specimens taken as bycatch had to be landed and sold. From 2011, live specimens must be released, whereas<br />

dead specimens can (not must) be landed and sold. Reporting was extended to include the number of<br />

specimens landed in addition to weight. From 2011, the regulations also include recreational fishing.<br />

In the Northwest Atlantic, shark fisheries management is underway in Canadian and US waters. An annual<br />

quota of 92t was adopted in US waters in 1999, under the Highly Migratory Species Fisheries Management<br />

Plan. This was reduced in 2008 to a TAC of 11t for all US fisheries, including a commercial quota of 1.7t,<br />

which often lead to the closure of the fishery before the end of the year. Since 2008, US Atlantic sharks must<br />

be landed with their fins naturally attached. The 1995 Canadian fisheries management plan limits number of<br />

licenses, types of gear, fishing areas and seasons, prohibits finning, and restricts recreational fishing to catchand-release<br />

only. Fisheries management plans for pelagic sharks in Atlantic Canada established nonrestrictive<br />

catch guidelines of 1500t for L. <strong>nasus</strong> prior to 1997, followed by a provisional TAC of 1000t for<br />

the period 1997–1999, based largely on historic reported landings and the observation that recent catch rates<br />

had decreased (DFO 2001). Following analytical stock assessments (Campana et al. 1999, 2001), the Shark<br />

Management Plan for 2002–2007 reduced the TAC to 250t, followed by a further reduction to 185t (60t<br />

bycatch, 125t directed fishery) from 2006 (Figure 20). Population projections indicate that the population will<br />

eventually recover if harvest rates are kept under 4% (~185 mt, DFO 2005b), but unregulated and unreported<br />

catches on the high seas jeopardize recovery (Campana and Gibson 2008, Figures 14 and 15).<br />

In 2006, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) adopted a<br />

moratorium on directed shark fishing until data become available to assess the impacts of fishing on sharks in<br />

the Antarctic region. The live release of sharks taken as bycatch is encouraged but not mandated<br />

Page 12 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 12<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

(Conservation Measure 32-18; CCAMLR 2006). The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission<br />

(WCPFC) will be responsible for pelagic shark management, but this is unlikely to be attempted during the<br />

early years of this Commission (Ministry of Fisheries 2006). Argentina requires live bycatch of large sharks to<br />

be released alive. Australia introduced legislation in 1991 preventing Japanese longliners fishing in the EEZ<br />

from landing shark fins unless accompanied by the carcass. They have not fished in the Australian EEZ since<br />

1996. Finning is prohibited in domestic Australian tuna longliners. New Zealand has included L. <strong>nasus</strong> in its<br />

Quota Management System (QMS) since 2004 with an unrestrictive TAC set at 249t (Sullivan et al. 2005),<br />

permitting finning and discard of carcasses.<br />

8.2 Population monitoring<br />

Routine monitoring of catches, collection of reliable data on indicators of stock biomass and good knowledge<br />

of biology and ecology are required. Most States do not record shark catch, bycatch, effort and discard data at<br />

species level or undertake fishery-independent surveys, preventing stock assessments and population<br />

evaluation. High seas catches are particularly poorly monitored (e.g. Campana and Gibson 2008). FAO<br />

FISHSTAT data are incomplete. Accurate trade data provide a means of confirming landings and an<br />

indication of compliance with catch levels, allow new catching and trading States to be identified, and provide<br />

information on trends in trade (Lack 2006). Trade data for porbeagle are, however, unreported except in the<br />

EU. FAO (2010) noted that a CITES listing is expected to result in better monitoring of catches entering<br />

international trade from all stocks and could therefore have a beneficial effect on the management of the<br />

species in all parts of its range. In the absence of a CITES listing there is no reliable mechanism to track<br />

trends in catch and trade of this species.<br />

8.3 Control measures<br />

International<br />

Other than sanitary regulations related to seafood products and measures that facilitate the collection of import<br />

duties, there are no controls or monitoring systems to regulate or assess the nature, level and characteristics of<br />

trade in L. <strong>nasus</strong>.<br />

Domestic<br />

The domestic fisheries management measures adopted by a few States described above cannot deliver<br />

sustainable harvest of L. <strong>nasus</strong> when stocks are exploited by several fleets, particularly in unregulated and<br />

unmonitored high seas fisheries. Even where catch quotas have been established, no trade measures prevent<br />

the sale or export of landings in excess of quotas. Otherwise, only the usual hygiene regulations apply to<br />

control of domestic trade and utilisation. STECF (2006) noted that although a CITES Appendix II listing<br />

alone would not be sufficient to regulate catching of porbeagle, it could be considered an ancillary measure.<br />

8.4 Captive breeding and artificial propagation<br />

No specimens are known to be bred in captivity.<br />

8.5 Habitat conservation<br />

Research in areas fished by the Canadian and French fleets and the results of tagging studies have identified<br />

some important L. <strong>nasus</strong> habitats, both within EEZs and on the high seas. Some habitat may be incidentally<br />

protected inside marine protected areas or static gear reserves, but there is no protection for critical high seas<br />

habitat.<br />

9. Information on Similar Species<br />

<strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> is one of five species in the family Lamnidae, or mackerel sharks, which also includes the White<br />

Shark Carcharodon carcharias and two species of Mako, genus Isurus. Salmon Shark <strong>Lamna</strong> ditropis is<br />

restricted to the North Pacific. Mako Isurus oxyrinchus may be misidentified as L. <strong>nasus</strong> in Mediterranean<br />

fisheries, although the identification of whole sharks is straightforward using existing keys.<br />

10. Consultations<br />

Page 13 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 13<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - prepared by Germany in January 2012<br />

11. Additional remarks<br />

11.1 CITES Provisions under Article IV, paragraphs 6 and 7: Introduction from the sea<br />

It is unclear whether introduction from the sea will be a significant issue for this species. Most target fisheries,<br />

even on the shelf edge, have been recorded inside EEZs. Pelagic Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese vessels,<br />

however, take porbeagle bycatch on the high seas, estimates for Japan ranging from 15t to 280t annually<br />

during 2000–2002 (DFO 2005b). A CITES Appendix II listing would require introductions from the sea to be<br />

accompanied by a non-detriment finding. They would have to be taken from a sustainably exploited high seas<br />

fishery, requiring management action by the appropriate Regional Fisheries Management Organisation. FAO<br />

(2010) considered that regulation of international trade through listing in CITES Appendix II could strengthen<br />

national efforts to keep harvesting for trade commensurate with stock rebuilding plans and improve the<br />

control of high seas catches through the use of certificates of introduction from the sea accompanied by non<br />

detriment findings.<br />

11.2 Implementation issues<br />

11.2.1 Scientific Authority<br />

It would be most appropriate for the Scientific Authority for this species to be advised by a fisheries expert.<br />

11.2.2 Identification of products in trade<br />

It will be important to develop species-specific commodity codes and identification guides for the meat and<br />

fins of this species. L. <strong>nasus</strong> meat, the product most commonly traded, is one of the highest priced shark meats<br />

in trade and often identified by name. The dorsal fin (with skin on) has a characteristic white rear free edge<br />

and a generic guide to the identification of shark fins is available (Deynat2010). Several research groups have<br />

developed species-specific primers and highly efficient multiplex PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction)<br />

screening assay for L. <strong>nasus</strong>, capable of distinguishing between Southern and Northern Hemisphere stocks<br />

(e.g. Shivji et al. 2002; Pade et al. 2006; Testerman et al. 2007). Cost per sample processed starts from<br />

US$20–60, depending upon condition of sample, less for large numbers. Turn-around time is in the region of<br />

2–7 days from receipt of sample, depending upon urgency. These tests are available and may be used to<br />

confirm identification and product origin for enforcement purposes.<br />

11.2.3 Non-detriment findings<br />

CITES AC22 Doc. 17.2 provides first considerations on non-detriment findings for shark species. The<br />

Spanish Scientific Authority (García-Núñez 2008) reviewed the management measures and fishing<br />

restrictions established by international organisations related to the conservation and sustainable use of sharks,<br />

offering some guidelines and a guide of useful resources. It also adapted to elasmobranch species the checklist<br />

prepared for making NDF by IUCN (Rosser & Haywood 2002). Similarly, the outcome of the Expert<br />

Workshop on Non-Detriment Findings (Anonymous 2008) points to the information considered essential for<br />

making NDF for sharks and other fish species, and also proposes logical steps to be taken when facing this<br />

task.<br />

Management for L. <strong>nasus</strong> would ideally be based upon stock assessments and scientific advice to allow stock<br />

rebuilding (where necessary) and ensure sustainable fisheries (e.g. through quotas or technical measures,<br />

including closed areas, size limits and the release of live bycatch). This is standard fisheries management<br />

practice – albeit currently not widely applied for this species. Other States wishing to export L. <strong>nasus</strong> products<br />

would also need to develop and implement sustainable fisheries management plans if NDFs are to be<br />

declared, and would need to ensure that all States fishing the same stocks implement and enforce equally<br />

precautionary conservation and management measures.<br />

12. References (see Annex 5)<br />

Page 14 of 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 14<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Annexes to Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - January 2012<br />

Annex 1.<br />

Figures and Tables<br />

Table 1. Indices of percentage decline illustrated in Figure 2 (see proposal p. 5)<br />

Table 2. <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> life history parameters<br />

Table 3. Summary of population and catch trend data<br />

Table 4. EU Commodity codes related to trade in <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>.<br />

Table 5. EU imports of porbeagle <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> products, products (fresh and frozen) by source<br />

countries/territories, value and weight, 2010 and 2011.<br />

Table 6. EU exports of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> products (fresh and frozen) by destination, value and weight,<br />

2010-2011.<br />

Figure 1. Porbeagle <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> (see proposal p. 1)<br />

Figure 2. Decline trends for porbeagle <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> stocks (see proposal p. 4)<br />

Figure 3. Global <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> distribution (Source: FAO FIGIS)<br />

Figure 4. FAO fishing areas<br />

Figure 5. Global reported landings (tonnes) of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> by major FAO fishing areas, 1950–2009.<br />

(Source: FAO FishStat) (Data will be updated at a later stage)<br />

Figure 6. Landings (tonnes) of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> from the Northeast Atlantic by major fishing States, 1950–<br />

2009. (Source: FAO Fishstat) (Data will be updated at a later stage)<br />

Figure 7. Landings (tonnes) of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> from ICES Areas (Northeast Atlantic), 1973–2009.<br />

(Source: ICES Working Group on Elasmobranch Fishes 2010) (Data will be updated at a later<br />

stage)<br />

Figure 8. Landings (tonnes) of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> by Norway in the Northeast Atlantic, 1926–2009. (Source:<br />

Norwegian fisheries data & ICES WGEF) (Data will be updated at a later stage)<br />

Figure 9. Landings (tonnes) of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> by Denmark in the Northeast Atlantic, 1954–2009.<br />

(Source: ICES Working Group on Elasmobranch Fishes) (Data will be updated at a later stage)<br />

Figure 10. Landings (tonnes) of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> by Faroe Islands in the Northeast Atlantic, 1973–2009.<br />

(Source: ICES WGEF and European Commission.) (Data will be updated at a later stage)<br />

Figure 11. French landings (tonnes) of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in the Northeast Atlantic, 1978–2009. (Source:<br />

ICES Working Group on Elasmobranch Fishes) (Data will be updated at a later stage)<br />

Figure 12. Surplus production age-structured model fits to French longline CPUE indices (assuming<br />

virgin conditions in 1926) for northeast Atlantic porbeagle shark. Source ICCAT SCRS/ICES<br />

2009.<br />

Figure 13. Depletion in total biomass (upper panel) and numbers (lower panel) for a surplus production<br />

age-structured model for Northeast Atlantic porbeagle shark. The dots indicated on the line<br />

correspond to depletion at the beginning of the modern period (1972) and current depletion<br />

(2008).Source ICCAT/ICES 2009.<br />

Figure 14. <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> landings in the Northwest Atlantic, 1961–2008 (excluding unreported high seas<br />

captures). (Source: Campana et al. 2010)<br />

Figure 15. Estimated trends in numbers of mature females (top), age-1 recruits (centre) and total<br />

number of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Canadian waters, 1960–2010, from four porbeagle population<br />

models (all show similar trajectories). (Source: Campana et al. 2010.)<br />

Figure 16. Comparison of recovery targets and trajectories for the Canadian porbeagle stock during<br />

2009–2100, obtained using Population Viability Analysis from four population models projected<br />

deterministically under four different exploitation rates (0% to 8% per annum). (Source:<br />

Campana et al. 2010.)<br />

Figure 17. New Zealand commercial landings of porbeagle sharks reported by fishers and processors<br />

(LFRR), 1989/90 to 2004/05. (Source Ministry of Fisheries 2008.)<br />

Figure 18. Unstandardised CPUE indices (number of <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> per 1000 hooks) for the New<br />

Zealand tuna longline fishery based on observer reports.<br />

Figure 19. Relative spawning stock biomass (SSB) trend for the catch free age structured production<br />

model, assuming virgin conditions in 1961, for southwest Atlantic porbeagle shark.<br />

Figure 20. Southern hemisphere landings of porbeagle <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>, 1990–2009 (FISHSTAT).<br />

Annexes p. 1 of 24<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 15<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)

Age at maturity<br />

(years)<br />

Annexes to Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - January 2012<br />

Size at maturity (total<br />

length cm)<br />

Maximum size (total<br />

length cm)<br />

Table 2. <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> life history parameters<br />

female: 13 years (North Atlantic); 15–<br />

18 years (SW Pacific)<br />

male: 8 years (North Atlantic); 8–11<br />

years (SW Pacific)<br />

female: 195 cm (SW Pacific), 230–<br />

260 cm (North Atlantic)<br />

male: 165 cm (SW Pacific), 180–<br />

215 cm (North Atlantic)<br />

female: 302, 357 cm (N Atlantic);<br />

240 cm (SW Pacific)<br />

male: 253, 295 cm (N Atlantic;<br />

240 cm (SW Pacific)<br />

Longevity (years) >25–46 years (Northwest Atlantic); ~65<br />

years (Southwest Pacific)<br />

Size at birth (cm) 58–77 (North Atlantic), 72–82 (Southwest<br />

Pacific)<br />

Average reproductive<br />

age/ generation time<br />

18 years (Northwest Atlantic); 26 years<br />

(Southwest Pacific)<br />

Gestation time 8–9 months<br />

Reproductive<br />

periodicity<br />

Annual<br />

Average litter size Four pups<br />

Annual rate of 5–7% (unfished, North Atlantic);<br />

population increase 2.6% (from MSY, southwestern Pacific<br />

Natural mortality 0.10 (immatures), 0.15 (mature males),<br />

0.20 (mature F) (Northwest Atlantic)<br />

(Data will be updated at a later stage)<br />

Annexes p. 2 of 24<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2, Annex 1 – p. 16<br />

AC26 Doc. 26.2<br />

Annex / Anexo /Annexe<br />

(English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais)<br />

Campana et al. 2008; DFO 2005; Francis et<br />

al. 2007<br />

Campana et al. 2008; DFO 2005; Francis et<br />

al. 2007<br />

Campana et al. 2008; Dulvy et al. 2008;<br />

Francis et al. 2007; Francis & Duffy 2005<br />

Campana et al. 2008; Dulvy et al. 2008;<br />

Francis et al. 2007<br />

Francis et al. 2008; DFO 2005; Dulvy et al.<br />

2008<br />

Francis et al. 2008; DFO 2005; Dulvy et al.<br />

2008<br />

Campana et al. 2008; DFO 2005; Francis et<br />

al. 2007<br />

Francis et al. 2008; Dulvy et al. 2008<br />

Campana et al. 2008; DFO 2005; Francis et<br />

al. 2007<br />

Campana et al. 2008; Smith et al. 2008<br />

Campana et al. 2001

Annexes to Draft Proposal to list <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong> in Appendix II - January 2012<br />

Table 3. Summary of population and catch trend data<br />

Year Location Data used Trend Source<br />

1933/37–<br />

2004/08<br />

NE Atlantic<br />

1936–2007 NE Atlantic<br />

1950/54–<br />

2004/08<br />

1986–2007 NE Atlantic<br />

1972–2007 NE Atlantic<br />

All Northeast<br />

Atlantic landings<br />

Norwegian<br />

landings<br />

87% decline in 5 yr average landings<br />

from historic baseline<br />

>99 % decline from historic baseline.<br />

Trend is the same if 5-year averages are<br />

used.<br />

NE Atlantic Danish fishery 99% decline from historic baseline<br />

Spanish longline<br />

bycatch CPUE<br />

French target<br />

longline CPUE<br />

1926–2008 NE Atlantic Stock assessment<br />

Various,<br />

1800–2006<br />

1950–2006<br />

1978–1999<br />

Mediterranean Records of <strong>Lamna</strong><br />

<strong>nasus</strong><br />

Ligurian Sea,<br />

Mediterranean<br />

Ionian Sea,<br />

Mediterranean<br />

1963–1970 NW Atlantic<br />

1961–2008 NW Atlantic<br />

1961–2005 NW Atlantic<br />

1961–2005 NW Atlantic<br />

1961–2005 NW Atlantic<br />