Porbeagle Shark Lamna nasus - The Shark Trust

Porbeagle Shark Lamna nasus - The Shark Trust

Porbeagle Shark Lamna nasus - The Shark Trust

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

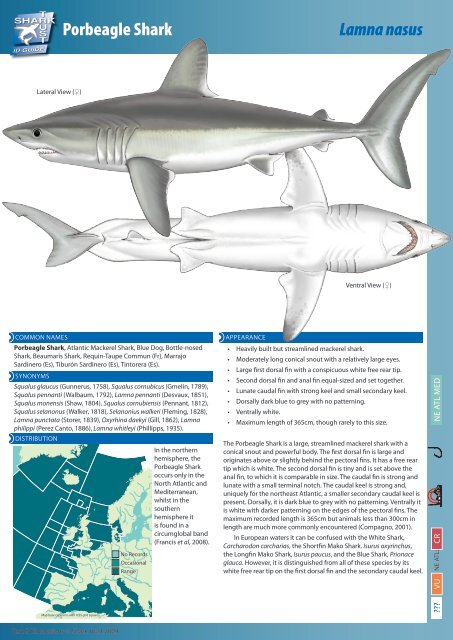

Lateral View (♀)<br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong><br />

COMMON NAMES<br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong>, Atlantic Mackerel <strong>Shark</strong>, Blue Dog, Bottle-nosed<br />

<strong>Shark</strong>, Beaumaris <strong>Shark</strong>, Requin-Taupe Commun (Fr), Marrajo<br />

Sardinero (Es), Tiburón Sardinero (Es), Tintorera (Es).<br />

SYNONYMS<br />

Squalus glaucus (Gunnerus, 1758), Squalus cornubicus (Gmelin, 1789),<br />

Squalus pennanti (Walbaum, 1792), <strong>Lamna</strong> pennanti (Desvaux, 1851),<br />

Squalus monensis (Shaw, 1804), Squalus cornubiensis (Pennant, 1812),<br />

Squalus selanonus (Walker, 1818), Selanonius walkeri (Fleming, 1828),<br />

<strong>Lamna</strong> punctata (Storer, 1839), Oxyrhina daekyi (Gill, 1862), <strong>Lamna</strong><br />

philippi (Perez Canto, 1886), <strong>Lamna</strong> whitleyi (Phillipps, 1935).<br />

DISTRIBUTION<br />

In the northern<br />

hemisphere, the<br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong><br />

occurs only in the<br />

North Atlantic and<br />

Mediterranean,<br />

whilst in the<br />

southern<br />

hemisphere it<br />

is found in a<br />

circumglobal band<br />

(Francis et al, 2008).<br />

Map base conforms with ICES grid squares.<br />

Text & Illustrations © <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> 2009<br />

No Records<br />

Occasional<br />

Range<br />

Ventral View (♀)<br />

APPEARANCE<br />

• Heavily built but streamlined mackerel shark.<br />

• Moderately long conical snout with a relatively large eyes.<br />

• Large first dorsal fin with a conspicuous white free rear tip.<br />

• Second dorsal fin and anal fin equal-sized and set together.<br />

• Lunate caudal fin with strong keel and small secondary keel.<br />

• Dorsally dark blue to grey with no patterning.<br />

• Ventrally white.<br />

• Maximum length of 365cm, though rarely to this size.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> is a large, streamlined mackerel shark with a<br />

conical snout and powerful body. <strong>The</strong> first dorsal fin is large and<br />

originates above or slightly behind the pectoral fins. It has a free rear<br />

tip which is white. <strong>The</strong> second dorsal fin is tiny and is set above the<br />

anal fin, to which it is comparable in size. <strong>The</strong> caudal fin is strong and<br />

lunate with a small terminal notch. <strong>The</strong> caudal keel is strong and,<br />

uniquely for the northeast Atlantic, a smaller secondary caudal keel is<br />

present. Dorsally, it is dark blue to grey with no patterning. Ventrally it<br />

is white with darker patterning on the edges of the pectoral fins. <strong>The</strong><br />

maximum recorded length is 365cm but animals less than 300cm in<br />

length are much more commonly encountered (Compagno, 2001).<br />

In European waters it can be confused with the White <strong>Shark</strong>,<br />

Carcharodon carcharias, the Shortfin Mako <strong>Shark</strong>. Isurus oxyrinchus,<br />

the Longfin Mako <strong>Shark</strong>, Isurus paucus, and the Blue <strong>Shark</strong>, Prionace<br />

glauca. However, it is distinguished from all of these species by its<br />

white free rear tip on the first dorsal fin and the secondary caudal keel.<br />

NE ATL MED<br />

CR<br />

NE ATL:<br />

??? VU

SIMILAR SPECIES<br />

Carcharodon carcharias, White <strong>Shark</strong><br />

Isurus oxyrinchus, Shortfin Mako <strong>Shark</strong><br />

Isurus paucus, Longfin Mako <strong>Shark</strong><br />

Prionace glauca, Blue <strong>Shark</strong><br />

(Not to scale)<br />

Supported by:<br />

Carcharodon carcharias,<br />

White <strong>Shark</strong><br />

Isurus paucus,<br />

Longfin Mako <strong>Shark</strong><br />

Text & Illustrations © <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> 2009<br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong><br />

<strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>,<br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong><br />

Isurus oxyrinchus,<br />

Shortfin Mako <strong>Shark</strong><br />

Prionace glauca,<br />

Blue <strong>Shark</strong>

TEETH<br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> teeth are moderately large and<br />

blade-like with lateral cusps. <strong>The</strong><br />

first upper lateral teeth have nearly<br />

straight cusps (Roman, Unknown).<br />

ECOLOGY AND BIOLOGY<br />

HABITAT<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> can be found from the surface to 715m in<br />

coastal and pelagic waters (Roman, Unknown). Tagging studies<br />

have revealed a preference for shelf waters, although one tagged<br />

individual travelled 1,800km into the mid-Atlantic. <strong>The</strong>re is only<br />

one record of a tagged shark crossing the Atlantic from Ireland<br />

to Canada and it appears that the two populations are separate<br />

(Francis et al., 2008). While it does not appear to enter freshwater,<br />

catches from a brackish estuary in Argentina have been reported<br />

(Roman, Unknown).<br />

In the southern hemisphere it may move further north, out of<br />

its usual range, during the cooler months but is not found further<br />

north than 35 o S during the summer. Around Australia it may move<br />

into subtropical waters during the winter. It appears to be limited<br />

to waters between 1–23 o C, with abundance declining above 19 o C<br />

(Francis et al., 2008).<br />

In the North Atlantic, temperatures of -1–15 o C have been<br />

recorded with a mean of 7–8 o C. Its abundance is also governed by<br />

seasonal variations with records of <strong>Porbeagle</strong>s moving north along<br />

the coast of North America during the spring and early summer<br />

with the return migration in late autumn (Francis et al., 2008).<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> appears to segregate by sex and size. In<br />

Spanish waters, males dominate catches over females in a ratio of<br />

2:1, while 30% more females than males are caught off Scotland. In<br />

the Bristol Channel, smaller individuals are found with a dominance<br />

of males over females (Francis et al., 2008). This segregation is likely<br />

to have evolved as a mechanism of reducing predation of neonates<br />

by adults and also to limit breeding to appropriate seasons (Roman,<br />

Unknown).<br />

DIET<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> is primarily a piscivore with teleost fish<br />

constituting 90% of the diet of some individuals. It has been<br />

reported that pelagic fish are preferred during the spring and<br />

summer when abundant. During the autumn and winter, groundfish<br />

are the dominant prey. (Roman, Unknown). Compagno (2001)<br />

lists the most common prey items as mackerels, pilchards and<br />

herring, various gadoids including cod, hakes, haddock, cusk, and<br />

whiting, and john dories, dogfishes and hound sharks (Squalus and<br />

Galeorhinus spp.), and squids (Compagno, 2001).<br />

Text & Illustrations © <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> 2009<br />

REPRODUCTION<br />

Species in the family lamnidae are viviparous with embryos<br />

nourished either by a continual supply of unfertilized eggs (oophagy)<br />

or through feeding on less developed siblings (adelphophagy, known<br />

only from the Sandtiger <strong>Shark</strong>, Carcharias taurus) (Martin, 1984). <strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> employs oophagy to supply nutrients to embryos<br />

once the original yolk-sac supply has been depleted. Its ovaries are<br />

well adapted to this task and may contain up to 200,000 unfertilised<br />

eggs, measuring 1.5–5mm in diameter (Lombardi, 1998).<br />

It has been reported from the northwest Atlantic that females<br />

mature at 200–219cm and 50% are mature by 208cm. Males<br />

mature at 155–177cm with 50% mature by 166cm. In the southern<br />

hemisphere off New Zealand, females mature at 170–180cm and<br />

males mature at 140–150cm (Francis et al., 2008).<br />

In the North Atlantic mating occurs in autumn and winter and<br />

the females give birth during spring and summer after an 8–9<br />

month gestation period. It appears that populations in the southern<br />

hemisphere may breed at different times but data is lacking. <strong>The</strong><br />

females give to birth to a litter of 1–5 pups, although 4 is normal with<br />

2 pups to each uterus. Each of these pups measures 58–67cm long at<br />

birth (Francis et al., 2008).

Supported by:<br />

COMMERCIAL IMPORTANCE<br />

One of the most valuable elasmobranch species to commercial<br />

fisheries, the <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> is taken across its range in targeted<br />

longline fisheries and its flesh is used for human consumption, its<br />

fins for sharkfin soup, its liver oil for vitamins and its carcass can<br />

be processed for fishmeal. It is also regularly taken as bycatch,<br />

particularly in tuna longline fisheries in the South Pacific but also in<br />

trawl, handline and gillnet fisheries. It is an important recreational<br />

species on both sides of the North Atlantic (Stevens et al., 2006).<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> has been fished commercially since the early<br />

1800’s, principally by Scandinavian fishers, to provide flesh for<br />

human consumption, fins for sharkfin soup, liver oil for vitamins<br />

and carcass’ for fishmeal (Gauld, 1989). Global catches peaked in the<br />

1960’s at around 9,000 tons, followed by a rapid decline to 1,300–<br />

2,600 tons in the 1990’s (Francis et al., 2008). Catches in the North<br />

Atlantic have varied wildly during the 20th century, particularly in<br />

the case of the Norwegian targeted fishery. In 1926, 279 tons were<br />

landed. This increased to 3,884 tons in 1933 followed by a sharp<br />

decline due to the reduction in fishing effort during the Second<br />

World War. In 1947, catches were back up to 2,824 tons but then<br />

declined steadily to 207 tons in 1970 and just 25 tons in 1994. <strong>The</strong><br />

fishery attempted to boost catches by moving across to the west<br />

Atlantic stock but had to switch focus to other species such as the<br />

Shortfin Mako <strong>Shark</strong>, Isurus oxyrinchus, and swordfish (Compagno,<br />

2001).<br />

Currently in the North Atlantic, the <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> is taken<br />

primarily in directed longline fisheries, although there is some<br />

bycatch from bottom trawls, handlines and gill nets. <strong>The</strong> majority of<br />

the catch in the southern hemisphere is bycatch from tuna longline<br />

fleets in the South Pacific and southern Indian Ocean, although<br />

there is a small Norwegian targeted fishery (Francis et al., 2008). <strong>The</strong><br />

only landings reported to the FAO from the southern hemisphere<br />

are from the New Zealand fishery, meaning that the fishing<br />

mortality for the southern stock is almost unknown (Compagno,<br />

2001).<br />

In the northeast Atlantic, the <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> is covered by EC<br />

Regulation No. 1185/2003 which prevents the removal of its fins<br />

at sea and the subsequent discard of the body. This applies to all<br />

vessels operating in EC waters, as well as to EC vessels operating<br />

anywhere (CPOA <strong>Shark</strong>s, 2009). In addition, a total allowable catch<br />

(TAC) applies to this species in European Waters. In 2008 this TAC<br />

was 581 tons. Despite scientific advice for a zero TAC for 2009, it<br />

was lowered by only 25% to 436 tons with a maximum landing<br />

size of 210cm designed to protect breeding individuals (European<br />

Commission, 2008). In 2010, the TAC was finally reduced to zero<br />

meaning the species cannot be landed by commercial fishers in the<br />

EU.<br />

IUCN RED LIST ASSESSMENT<br />

Vulnerable (2005).<br />

Critically Endangered in northeast Atlantic.<br />

THREATS, CONSERVATION, LEGISLATION HANDLING AND THORN ARRANGEMENT<br />

Text & Illustrations © <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> 2009<br />

• Handle with care.<br />

• Large shark.<br />

• Powerful jaws and sharp teeth.<br />

• Abrasive skin.<br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong>

REFERENCES<br />

<strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong><br />

COMPAGNO, L. J. V. 2001. <strong>Shark</strong>s of the World: An Annotated and<br />

Illustrated Catalogue of <strong>Shark</strong> Species Known to Date. Volume<br />

2. Bullhead, Mackerel and Carpet <strong>Shark</strong>s (Heterodontiformes,<br />

Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). FAO. Rome, Italy.<br />

FRANCIS, M. P., NATANSON, L. J., CAMPANA, S. E. 2008. <strong>The</strong> Biology<br />

and Ecology of the <strong>Porbeagle</strong> <strong>Shark</strong>, <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>. In: Camhi,<br />

M. D., Pikitch, E. K., Babcock, E. A. (Eds.) 2008. <strong>Shark</strong>s of the<br />

Open Ocean: Biology, Fisheries and Conservation. Blackwell<br />

Publishing Ltd. Oxford, UK.<br />

GAULD, J. A. 1989. Records of <strong>Porbeagle</strong>s Landed in Scotland, with<br />

Observations on the Biology, Distribution and Exploitation<br />

of the Species. Department of Agriculture and Fisheries for<br />

Scotland.<br />

LOMBARDI, J. 1998. Comparative Vertebrate Reproduction.<br />

Springer. New York, USA.<br />

MARTIN, R. A. 1994. From Here to Maternity. Diver Magazine, April<br />

1994.<br />

ROMAN, B. Unknown. <strong>Porbeagle</strong>. Florida Museum of Natural<br />

History. www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/.<br />

STEVENS, J., FOWLER, S.L., SOLDO, A., MCCORD, M., BAUM, J.,<br />

ACUÑA, E., DOMINGO, A., FRANCIS, M. 2006. <strong>Lamna</strong> <strong>nasus</strong>. In:<br />

IUCN 2008. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. www.<br />

iucnredlist.org.<br />

Text & Illustrations © <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> 2009<br />

Text: Richard Hurst.<br />

Illustrations: Marc Dando.<br />

Citation<br />

<strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>; 2010. An Illustrated Compendium of <strong>Shark</strong>s, Skates, Rays<br />

and Chimaera. Chapter 1: <strong>The</strong> British Isles and Northeast Atlantic. Part<br />

2: <strong>Shark</strong>s.<br />

Any ammendments or corrections, please contact:<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Shark</strong> <strong>Trust</strong><br />

4 Creykes Court, <strong>The</strong> Millfields<br />

Plymouth, Devon PL1 3JB<br />

Tel: 01752 672008/672020<br />

Email: enquiries@sharktrust.org<br />

For more ID materials visit www.sharktrust.org/ID.<br />

Registered Company No. 3396164.<br />

Registered Charity No. 1064185